T. Corey Brennan

The Ancient Romans, in both the Republic (as far back as we can reliably trace) and Empire, made a familiar and highly effective spectacle out of bundling wooden rods and a single-bladed axe with leather straps into a ‘fasces’.[1] They presented this instrument as a mobile kit for punishment, one intended to induce feelings of respect for the relevant authority as well as fear. Ancient tradition is unanimous that twelve attendants known as ‘lictors’ each carried these fasces already in the pre-Republican period, walking in procession before the old kings of Rome. They used the insignia to mark the king’s status as a holder of imperium (full civil and military power) and, with it, his capacity to inflict either corporal or capital punishment.

The Fasces from Etruria to Rome and Byzantium

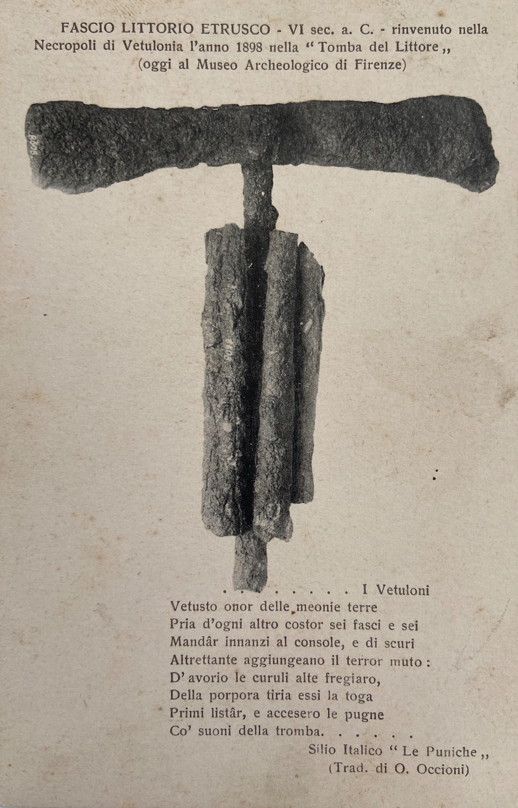

Tradition also held that Rome of the kings had appropriated this institution from the Etruscans. Some authorities, Livy among them, dated the borrowing as far back as Rome’s legendary founder Romulus. The discovery in 1898 of a miniature fasces with double-headed axe in a mid-7th-century BC tomb at Vetulonia, in the Maremma region of Tuscany, spectacularly confirmed the Romans’ basic understanding of the emblem’s origin. The find also suggested that Rome’s first Etruscan king, Tarquinius Priscus (whose reign is conventionally assigned to 616–579 BC), may well have paraded with the fasces, as our ancient literary authors believed.

Of course, our sources on Rome’s monarchy were writing centuries after the events they describe. Although they happen to get the provenance of the fasces right, ancient writers almost certainly undervalue the level of terror this severe Etruscan institution produced when imposed on a native Latin community at Rome. Indeed, it was so effective that when the Romans replaced their monarchy with a Republic headed by two annual consuls (traditionally dated to 509 BC), they are said to have kept the lictors and fasces as the principal marker of legitimate power— which the consul Lucius Iunius Brutus immediately used to behead his own sons, seditious supporters of a return to Etruscan rule. This legendary tale is a useful one, for it posits the precise moment when the Romans claimed the fasces as their own.

Rome’s annalistic historians presented the remainder of 509 BC as the occasion for a thorough revamping of the fasces, with the aim of asserting tighter public control of the insignia. Henceforth, we are told, the two consuls had to take turns presenting the full regal kit to denote precedence, remove the axes from their bundles within the city, and dip the insignia in assemblies to show deference to the Roman citizenry, who now received the right of appeal against summary execution. Whatever the actual dates of these measures, they most certainly existed in the historical period, had an exceptionally long life, and demonstrably set the tone for Rome’s political culture. There may have been other Republican reforms of the fasces, unmentioned in our sources. One which seems conceivable for the early period on the basis of the archaeological evidence from Vetulonia is that the Romans modified the regal fasces by splitting a double-headed axe into two, allowing the annual pairs of consuls to show just a single blade in each of their bundles.

Our sources for the Republic have little interest in the development of the fasces as a topic in itself, beyond the year 509 BC, which was thought to have seen the establishment of the consulship and (almost immediately) the reforms of its powers and insignia. Still, it appears that the 4th-century BC reimagining of imperium—seen in the invention of the praetor as a lesser colleague of the consul, the extension of commands beyond a year, and the possibility of a consul delegating his imperium to a private citizen—marked a decisive break with the regal-era notion that a dozen lictors with fasces expressed the sum of legitimate power. The extended emergency of the Second Punic War (218–201 BC) against Hannibal prompted Rome’s Senate to devise other extraordinary ways to give out imperium, including at the consular level.

Adding magistrates and quasi-magistrates to the roster of imperium holders meant more fasces, and more lictors. A rough and ready calculation for the year 191 BC suggests a total of at least 132 lictors with fasces in the city and the field. The numbers demonstrably ballooned further in the later Republic, when certain individuals not holding imperium started to get the fasces, especially in the early Empire. A new inscription from around AD 76, during the reign of the emperor Vespasian, tells us that the pool of lictors at Rome available for duty now numbered 370. These figures underline how common the frightening spectacle of fasces must have been in all historical eras, especially in the city of Rome, which served as both the seat of government and the point of departure for regular commands.

Lictors with fasces functioned as the extension of the person of their superior. But the literary evidence suggests that they were notorious for engaging in gratuitous brutality on top of their fearsome official functions, which allowed them even to enter private residences. Class prejudice in our sources surely plays a role here: although slaves were excluded from serving in this role, freed slaves were not. If we were to take Christian polemicists at their word, it would seem that, by later antiquity, lictors could be lumped together with torturers and executioners. Fortunately a sizeable corpus of (mostly) imperial-era inscriptions that commemorate lictors offers a corrective on this view. The epigraphic evidence shows that these attendants enjoyed a privileged status in which they took considerable pride, and some were able to amass enough wealth to become patrons of corporations or whole communities.

In truth, the first opportunity to speak with real confidence about the nature and conventions of the fasces comes only with the late 3rd and early 2nd centuries BC. That is the period when writers start producing historical works about Rome, and artists offer us our first glimpses of the emblem. When the institution comes into view for us, it appears quite evolved – and terrifying. That emerges from a 2nd-century BC mural painting from the Esquiline in Rome which depicts lictors in distinctive dress menacingly parading in triumph, and a coin (to be dated 110/109 BC) which represents a lictor about to dole out punishment. For Rome’s magistrates, accompaniment by lictors with the fasces was the chief sign that one held the chief civil and military power (imperium), and the dismissal of those attendants formally signalled departure from office. That is true for the imperial era as well.

Even in the mid-Republic the fasces show a refined symbology. A monumental relief sculpture near Rome – to be dated c.175 BC – presents simply 12 inverted fasces to communicate the death of a consul in office. In the mid-2nd-century BC, the Greek historian Polybius takes an interest in how the Romans used differing numbers of fasces to distinguish its highest offices from each other, including in the purely ceremonial realm of funerary processions. Indeed, Polybius demonstrates that the right to hold funerals involving faux fasces was a principal means by which families descended from consuls (i.e. ‘nobles’) distinguished themselves from others in Rome. These spectacles must have grown more and more common once they also started marking the deaths of noble women (attested by 91 BC). Plainly they also aimed at producing a strong emotional effect in the Roman public. We are told that the funeral of the dictator Sulla in 79 BC even featured a large, combustible image of a lictor (surely) holding a fasces.

Display of the fasces – both authentic ones and ceremonial simulacra – continuously and forcefully reinforced power relations between higher and lower officials, magistrates and non-magistrates, nobles and non-nobles, citizens and non-citizens, and even heightened class consciousness and distinctions among women. (Lictors were forbidden to touch ones deemed respectable.) It seems fair to say that non-Romans hated the symbol. Already in the mid-2nd century BC, Polybius counts it as the height of Greece’s misfortune that its free cities were compelled to admit Roman rods and axes within their gates. It was essential to an offical’s dignity that he leave the lictors who carried his fasces to do their always unpopular and sometimes bone-chilling physical work, and not personally engage himself. Conversely, when lictors saw their fasces smashed or stolen, the disgrace rebounded onto their superior – especially if they could not protect his physical person.

It is telling that moneyers of the Republic only sporadically include the fasces in their designs minted in Rome, and just once as an abstract symbol of state power – on the reverse of an obnoxious issue of 70 BC that emphasizes Rome’s dominance over its recently rebellious Italian allies. Rome’s emperors from Augustus through Nerva (i.e., 27 BC–AD 98) essentially avoid depicting the fasces on their coins, at Rome or in the provinces. The reason must be that the insignia primarily transmitted terror. In the 2nd century AD, minters for Trajan, Hadrian and Antoninus Pius revisited the fasces as a design motif, but with an emphasis on the lictors who carried them, either in ensemble scenes featuring the emperor, or acting as instruments of imperial philanthropy.

By the early 3rd century AD, a coin issue reveals that the fasces had received a makeover, now as long curved rods with non-functional axe heads. This is the form that persists through late antiquity, certainly well into the 6th century AD in both west and east. Carolingian knowledge of the insignia percolated into an (admittedly isolated) representation of the fasces in early-11th-century Anglo-Saxon religious art. Although the fasces proper do not play a major part in Byzantine ceremonial practices, lictor-like attendants with axes, twelve in number, show up in Constantinople at the coronation of emperor Manuel II Palaeologus in the year 1391. All of this is powerful evidence for the tenacity of the basic institution.

Post-Antique Emphasis on the Fasces as Emblem

In the medieval period, the word ‘fasces’ never fully fell out of Latin use, at least in a general sense of “supreme power” or “official honors”. Nor did the term ‘lictor’, because of its appearance in scripture, which preserved understanding of this attendant’s punitive role. Renaissance humanists mostly grasped the meaning of the ‘fasces’ that they encountered in Classical texts. However, artistic representations of the fasces were slow to come – not until the last quarter of the 15th century, where they start to pop up in various media to signifiy, however vaguely, the exercise of authority and the administration of justice.

The artist Raphael (1483–1520), however, took a pronounced interest in the details of the Roman fasces, which he prominently incorporated into two high-profile Vatican commissions. Those in turn spectacularly reintroduced the fasces into the iconographic mainstream. In the decades to follow, papal efforts to control the administration of law in Rome culminated in a celebratory painting with – for the first time – fasces as a key component in an elaborate allegorical scene. It was a powerful cardinal-nephew of Pope Paul III Farnese (reigned 1534–49) who commissioned this piece in 1544 from Giorgio Vasari (1511–74). Through this artist’s rendering of “Farnese Justice”, the fasces entered the rapidly expanding repertory of “emblems”, i.e., symbolic images with a moralizing purpose, very much a growth industry in the first half of the 16th century. Oddly enough, although the Church has no relationship whatsoever to the fasces, fully four Popes over the next two centuries had their tombs adorned with the rods and axe as a symbol of justice, starting with that of Paul III himself.

By the mid 17th century, we find representations of the rods with axe regularly evoking memories not just of Roman rule, but also of a popular but decidedly non-pertinent Aesop fable featuring an old man, his quarrelsome sons, and a bundle of sticks. The point of the tale is that one can break rods easily one at a time, but not when bound together – a visual lesson of the power of unity. Already in the first decades of the 16th century, school texts had made the story common knowledge, sometimes supplying as its moral the Roman historian Sallust’s observation that “with harmony small matters grow, with discord great ones are ruined.” In the mid 1540s, Vasari twice created an allegorical figure of Concord with sticks directly inspired by Aesop.

But what really propelled the fusion of Roman fasces and Aesopian sticks was the Nova Iconologia of Cesare Ripa (1555–1622), a compilation of emblems first published in anillustrated edition in 1603. There both Justice and Concord suggestively receive as their attributes a fascio delle verghe (“bundle of sticks”). Later editors of Ripa completed the conflation, most notably a 1643 French translation that pictured Concord shouldering a double-axed fasces, dragging in both Aesop and Sallust to explain the novel image. At that very time in France, the powerful cardinal and statesman Jules Mazarin (1602–61, chief minister to the crown from 1642) was shamelessly exploiting the fasces, ostensibly as a family heraldic emblem but with the effect of creating a personal brand. Mazarin attracted many encomiasts, who did much to promote the emphatically non-Roman idea that the fasces represented unity, and good government in general.

In a sense, this whole understanding of the fasces culminates in a bronze full-length portrait statue of Louis XIV (reigned 1643–1715), dedicated in 1689, which still stands today in the courtyard of Paris’ Musée Carnavalet. Here the sculptor Antoine Coysevox (1640–1720) portrayed the king in a Roman cuirass, resting his left arm on an axeless fasces topped by a helmet. In its context, the fasces conveys a balanced message of strength, dominion, moderation, and unity through reconciliation, while also rekindling memories of Mazarin’s own policies as advisor to the king. The Old Regime in France however did not sustain this focus on the fasces as a political emblem. Nor in this general period do other nations show much interest in putting the fasces on civic coats of arms, flags, coins, and the like. Even in the 1760s, when the antiquarian obsessions of the Neoclassical movement were at their peak, the fasces seemed fated to find itself just one derivative antique decorative element among many.

In a remarkable coincidence, 100 years to the day after the dedication of Coysevox’s statue of Louis XIV, on 14 July 1789, about a thousand insurrectionists in Paris attacked and captured the royal fortress of the Bastille. This set off France’s explosive Revolution which spelled the end of the monarchy. It took only a few weeks for the revolutionaries to choose the fasces as a symbol of their movement’s strength, power, commitment to justice, unity and – with a conscientious nod to the tradition on the insignia in Rome’s Republic – dependence on the assent of the people. When combined with a Roman freedman’s cap, they meant for the fasces to connote liberty too.

In 1792, in a first for any nation, the fasces figured in the semi-official seal of the new revolutionary state. There a seated female Liberty rests her left hand on the rods and axe, in what seems to be a direct and pointed quotation of the gesture of the 1689 Louis XIV statue. In 1793, a large ephemeral sculpture by Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825) of Hercules similarly touching the fasces struck some as an even more suitable design for a seal. The Greek hero Hercules of course has no link whatsoever to the Roman fasces, but it can be shown that in France he had a tenuous one with the Aesopic sticks.

Napoleon Bonaparte largely turned his back on the fasces in promoting his powers under the Consulate (1799–1804) and Empire (1804–15). However the spirit of the revolutionary coin types with fasces had a certain influence in the Americas even beyond France’s colonies in the New World, finding a place on the money of Mexico (1823–63), then Ecuador and Chile (after 1830). And the symbol finally won out in France itself in 1848, when the Second Republic adopted a Great Seal that showed a seated Liberty holding a spear-topped fasces among other attributes – a design used in France to the present day.

In North America, the distinctly non-Roman theme of the fasces representing unity made its own inroads. Already in May 1775, at the Second Continental Congress, one delegate was mooting the fasces as a symbol for the union of thirteen rebellious British colonies that would form the United States. Thomas Jefferson for his part preferred Aesop’s “father presenting the bundle of rods to his sons” as a device. What positively secured the fasces’ role in American symbology was this Congress’ decision in August 1776 to adopt E pluribus unum (Latin for “out of many one”) as a national motto. Although the new nation’s official seal (adopted 1782) did not include the fasces, it soon featured prominently in the repertoire of patriotic images.

Particularly important in promoting the image was the French artist Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741–1828). His sculptural portrait (begun 1785, signed 1788) of a relaxed George Washington resting his left arm on a tall axeless fasces – again, one thinks of the statue of Louis XIV at Musée Carnavalet – strongly influenced other artists’ depictions of the war hero who was elected first president of the United States (1789–97). Indeed, just weeks after the new United States constitution took effect (4 March 1789), the emblem found also an official place in American political life: the House of Representatives as one of its first acts adopted a fasces-like mace to serve as the badge of its Sergeant-at-Arms.

The story of the American fasces took another turn after the year 1789, the year which also saw France erupt in revolution. Put briefly, America’s early leaders, architects and artists leveraged direct knowledge of Classical antiquity (including that fable in Aesop involving a fasces-like bundle of sticks), but also observed what individuals in Britain and France had made and were making of the emblem in the public sphere. Indeed, a major role in this iconographic effort was played by foreigners, such as the French-born artist Maximilian Godefroy (1765–1840), who designed a gargantuan “Fascial” war memorial for the city of Baltimore (1815); the British medallist Thomas Halliday (1771–1844), who engraved a memorable commemoration of Washington with axed fasces (1816); and the Italian-born sculptor Enrico Causici (1790–1833), who was the first to introduce a representation of the fasces – in this case, bound with a rattlesnake – into the United States Capitol building (1817–19). One did not need expert acquaintance with the fasces to use it as a symbol, as much later the experience of the US dime designer Adolph A. Weinman (1870–1952) demonstrates, who erroneously thought a “battle-axe” was inserted in the bundle of the fasces he used for the “Mercury” ten-cent piece first issued in 1916.

Starting in the early 1830s, escalating conflict over slavery raised questions about the long-term stability of the American union. As the political atmosphere became more and more heated, it caused the fasces – now widely understood as the unity symbol par excellence – to proliferate, in everything from campaign broadsides to high art. By the mid 1850s, Southerners seem to have regarded the fasces, especially when joined with a liberty cap, as promoting the abolitionist cause. For instance, in 1854–5, we find the Mississippian Jefferson Davis (1808–89, later president of the Confederate States in 1861–5) trying to nix their inclusion as decorative elements of the Capitol building extension he was then supervising. Once actual civil war broke out between North and South in 1861, and especially after the assassination of United States president Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, the emblem grew only more powerful as a marker of American union. Decades later, it was specifically the fasces that the designers of the Lincoln Memorial (dedicated in 1922) chose as a main design element, multiplying and magnifying axeless bundles in their tribute to the slain president who had preserved the United States.

The Radical Reinterpretation of the Fasces in Mussolini’s Italy

The fasces readily presented itself as a symbol of unity also for the Kingdom of Italy, established definitively after an open struggle that stretched from 1848 to 1870. Somewhat surprisingly, none of the many activist Italian political groups of the late 19th and earlier 20th centuries that called themselves fasci (“bundles”) exploited the Roman device in their public messaging until 1919. In that year, the newspaper editor Benito Mussolini (1883–1945), as founder and leader of the “Italian Fasci of Combat”, embraced the (previously pejorative) tag “fascisti” for his supporters, and used a threatening representation of the fasces to identify his party’s candidates in a November general election. Use of the historical Roman emblem served as branding for his rapidly growing party, and to a stunning degree also helped valorize its violent methods, which intensified especially from Spring 1920.

After his movement’s largely bloodless “March on Rome” (28–30 October 1922) that felled the elected government, Mussolini – now as prime minister – set out immediately to force the fasces into every crevice of Italian daily life, from coinage and postage stamps to cigarette packaging. In the first half of 1923, the Fascist-led government tasked a leading archaeologist with divining the most “authentic” form of the Roman fasces – not so much out of genuine academic curiosity, but surely to set a single official form as the basis for a visual identity system. Amazingly, one fringe group of occultists sought to counter this effort by creating what they regarded as a spiritually supercharged fasces, topped allegedly by an Etruscan axe-head, which one of its members managed to present to Mussolini at a high-stakes event which guaranteed maximum international press. The ploy didn’t work, and Italy’s new nickel coinage with an antiquarian-derived Roman fasces went into mass production in Summer 1923.

All that proved to be just the first strides of a 20-year program to makes the fasces ubiquitous in Italy and the territories it colonized in Africa. Mussolini’s regime’s relentless focus on the fasces, and propagation of the image on a massive scale (with individual items ranging in size from lapel pins to entire structures) had no close parallel in world history – not in the Roman empire, where we never find the frightening image of a free-standing fasces on a coin, nor even in the feverish production of French Revolutionary iconography. In addition, Mussolini seems to have been the first statesperson ever to interpret the fasces as an instrument for imposing political unity by means of authority. (Everyone else had it the other way around.) It also was a special innovation of Mussolini to idealize the humble lictor who lugged the fasces, and raise him to prominence. The not so subtle suggestion here was that all elements of Italian society should model their behavior on that of the lictor, and selflessly and energetically carry forward the standard of fascismo.[2]

The defeat of the Axis powers in 1945 occasioned a comprehensive purge of the Nazi swastika emblem, and sent the image of the fasces sharply in retreat – even in the United States, where soon after the war’s end it was dropped from the long-established (since 1916) ten cent piece. However Italy developed no masterplan to address its now-ubiquitous Fascist symbols. Indeed, by 1953, its national Olympic committee was touting Rome’s old Foro Mussolini as an ideal site for the 1960 Summer Games. And once it won its bid, it made only a belated and feeble effort (quickly abandoned) to mitigate the effect of the hundreds of fasces embedded in the mosaic walkway that led to the principal stadium, which are still intact today. That said, in the post-World War II era – with the exception of a provocative twinned public sculpture (2001) on university campuses in Paisley and Princeton – no-one has been putting up new fasces in public art.

An Irreparably Tainted Symbol

For a succinct summary of the current situation of the fasces as symbol, especially in the United States, it is hard to better a reference entry on the website of the ADL (founded in Chicago in 1913 as the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith). In 350 words, under the heading “General Hate Symbols”, a clear and well-informed article scrupulously takes the reader from Ancient Rome, “whose leaders used it as a symbol of authority and power,” to the present moment. The main point of the article is to explain how the fasces earned its invidious designation, over and above Mussolini’s adoption of the device. “In the decades after World War II,” the ADL author explains, “many Nazi symbols were adopted by American neo-Nazis, but the fasces did not experience the same popularity…” However the ADL site identifies (and illustrates) the logos of five separate American white supremacist groups that currently display the fasces. “Beginning in the late 2000s,” we are told, “more American white supremacists turned to the fasces as a symbol, possibly because it did not have the strong negative connotations of the swastika and because extremists could defend their use of the fasces by pointing to its role in the symbology of the U.S. government.”

My hope is that my new book on the fasces, which surveys the meaning and interpretation of this emblem across a period of almost 2,700 years, shows that we are now a full century past the point where one can argue that the primary associations of the symbol are benign.

T. Corey Brennan is a professor of Classics at Rutgers University (New Brunswick, NJ), the founder and editor of the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi, and author of The Fasces: A History of Ancient Rome’s Most Dangerous Political Symbol (Oxford UP, 2022). He has written previously for Antigone about the Casino dell’Aurora.

Notes

| ⇧1 | This article was originally published in Swedish as “Fasces – 2700 år av det antika Roms mest framträdande politiska symbol” in Medusa: Svensk tidskrift för antiken (2022:2) 1–11. The editorial board of Medusa is warmly thanked for allowing the republication of this piece in English. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | For the fasces in Mussolini’s Italy, please see further my article on the Oxford University Press blog. |