The twilight years of the Heian Period of Japan (late 12th century) mark the high-point of the refined Imperial Court, its aristocracy and their literary culture. Poetry at this time, epitomized by the Hyakunin Isshu, was a popular past-time and frequent means of corresponding between men and women (often on the sly). A person’s career or reputation could be made or broken by a skillful, or clumsy, poem. Many of the ladies-in-waiting serving the court aristocracy would also go on to become famous writers in Japanese literature:

- Lady Murasaki (Japanese: murasaki-shikibu 紫式部) – who wrote the first Japanese novel, the Tales of Genji, and her own diary is a fascinating read. She is part of the social circle around Empress Shōshi. She is also known for poem 57 in the Hyakunin Isshu anthology.

- Sei Shonagon – who wrote the Pillow Book, a free-form thought about the minutia of Heian Period society. Sei Shonagon was part of a rival social circle centered around Empress Teishi. She is known for poem 62 in the Hyakunin Isshu.

- Akazome Emon – another accomplished poet in the same social circle as Lady Murasaki. She composed poem 59 of the Hyakunin Isshu among her many other accomplishments.

And finally we come to perhaps the most the most controversial, and yet one of the most brilliant ladies among this generation of ladies-in-waiting turned writers: Lady Izumi. In Japanese she is called Izumi Shikibu (和泉式部).

Like all women at the time, her real name is not known. She is named after her husband’s region of administration (Izumi province), and her father’s role in the Imperial court as master of ceremonies (shikibu 式部). Lady Izumi was born into the elite aristocracy in Heian society of the time, but she distinguished herself both with her particular skill in poetry and with her tendency to get involved in scandalous relationships.

While unhappily married to her husband, Tachibana no Michisada, she had an affair with Prince Tametaka, the third son of Emperor Reizei, which caused her to be divorced and shunned by her family. Her ex-husband also took custody of their only child, a daughter named Koshikibu no Naishi (poem 60 in the Hyakunin Isshu). However, before long her lover Prince Tametaka died due to illness.

Later, Prince Tametaka’s brother Prince Atsumichi approached Lady Izumi and a romantic relationship began. Lady Izumi’s “Diary of Lady Izumi” (izumi shikibu nikki 和泉式部日記) covers this period of time, and their correspondences to one another. For example, she composed the following as a reply to Prince Atsumichi:

| Japanese | Romanization | English |

| 薫る香に | Kaoru ka ni | Rather than recall |

| よそふるよりは | yoso uru yori wa | in these [tachibana] flowers |

| ほととぎす | hototogisu | the fragrance of the past, |

| 聞かばや同じ | kikaba ya onaji | I would like to hear this nightingale’s voice, |

| 声やしたると | koe yashitaru to | to know if his song is as sweet. |

She also left behind many romantic poems such as this one (undated, so it’s unclear who he is), which I was surprised to see quoted in the drama Thirteen Lords of the Shogun:

| Japanese | Romanization | English |

| 黒髪の | Kuro kami no | My black hair’s |

| 乱れても知らず | midarete shirazu | in disarray — uncaring |

| うち臥せば | uchi fuseba | he lay down, and |

| まづかきやりし | mazu kakiyarishi | first, gently smoothed it: |

| 人ぞ恋しき | hito zo koishiki | my darling love. |

Since she was divorced anyway, she moved in with the Prince and her relationship with Prince Atsumichi was an open scandal for the Court. They would often be seen riding his carriage through the capitol. Prince Atsumichi’s wife was furious about the affair, and returned to her family, while public criticism of the couple became increasingly harsh and unavoidable.

In the end, Prince Atsumichi, like his brother, died from illness at the age of 27. Lazy Izumi was once again heartbroken.

By this point, Lady Izumi had few options, and no support from her family, so she was taken in as a lady in waiting for Empress Shoshi,1 where she served alongside another notable ladies Akazome Emon and Lady Murasaki. Empress Shoshi’s father, the ambitious Fujiwara no Michinaga, wanted to gather as much talent under his household as he could. However, Lady Murasaki didn’t think too highly of her:

Izumi Shikibu is an amusing letter-writer; but there is something not very satisfactory about her. She has a gift for dashing off informal compositions in a careless running-hand; but in poetry she needs either an interesting subject or some classic model to imitate. Indeed it does not seem to me that in herself she is really a poet at all.

— trans. Waley, “Diary of Lady Murasaki”

Later, Lady Izumi married Fujiwara no Yasumasa and moved to the provinces, and she was reunited with her only daughter (now in her 20’s). Tragedy struck yet again as her daughter died soon after the reunion, leaving behind two children of her own. Lady Izumi was devastated by this loss, but thinking of her grandchildren, she wrote:

| Japanese | Romanization | English |

| 留め置きて | todome okite | Left behind [grandmother and grandchildren] |

| 誰をあはれと | tare wo aware to | whose loss do you |

| 思ひけん | omoi ken | think is more pitiful? |

| 子はまさるらん | ko wa masaruran | The children’s loss is worse |

| 子はまさりけり | ko wa masarikeri | Indeed, the children’s loss is worse. |

By this point, she devoted herself to the Buddhist path as a lay nun named Seishin Insei Hōni (誠心院専意法尼). One of her last poems she composed, poem 56 in the Hyakunin Isshu, is:

| Japanese | Romanization | English |

| あらざらむ | Arazaran | Among my memories |

| この世の外の | Kono yo no hoka no | of this world, from whence |

| 思ひ出に | Omoide ni | I will soon be gone, |

| 今ひとたびの | Ima hitotabi no | oh, how I wish there was |

| 逢ふこともがな | Au koto mo gana | one more meeting, now, with you! |

This poem, based on Japanese commentaries I’ve read, wasn’t meant to be a simple chat, she was likely missing someone she was still intimately involved with, though it’s unclear who.

Lady Izumi is a fascinating figure to me. She was obviously quite attractive. In a very closed, and high-scrutinized society as the Heian-era court aristocracy, multiple men of very high rank risked considerable scandal just to be with her. In layman’s terms, men of the time thought she was really hot.

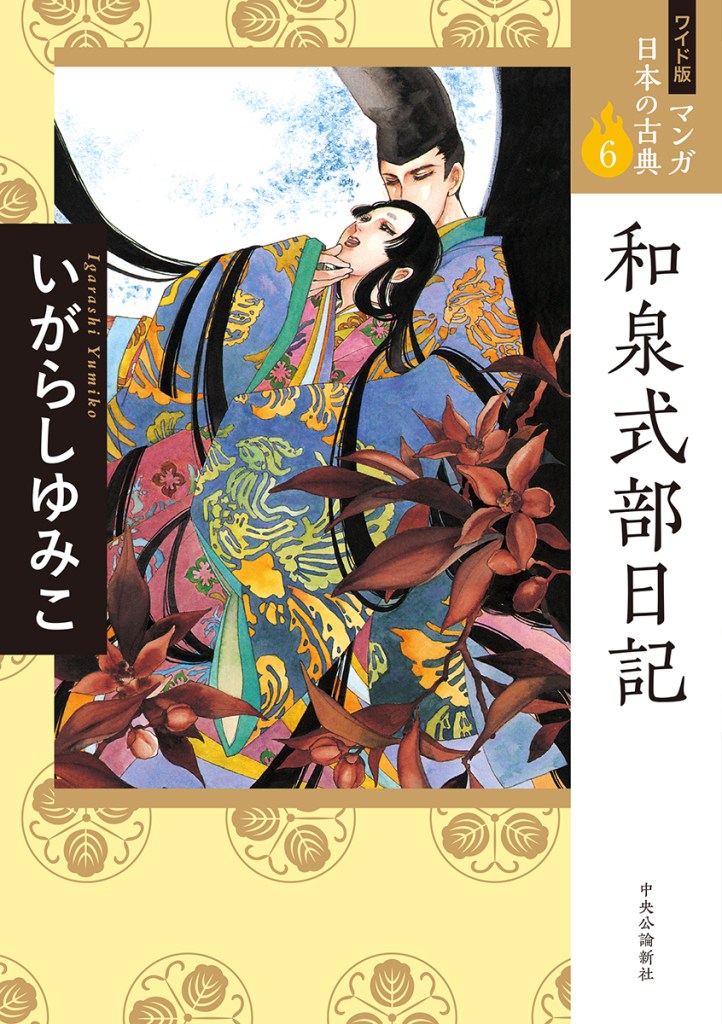

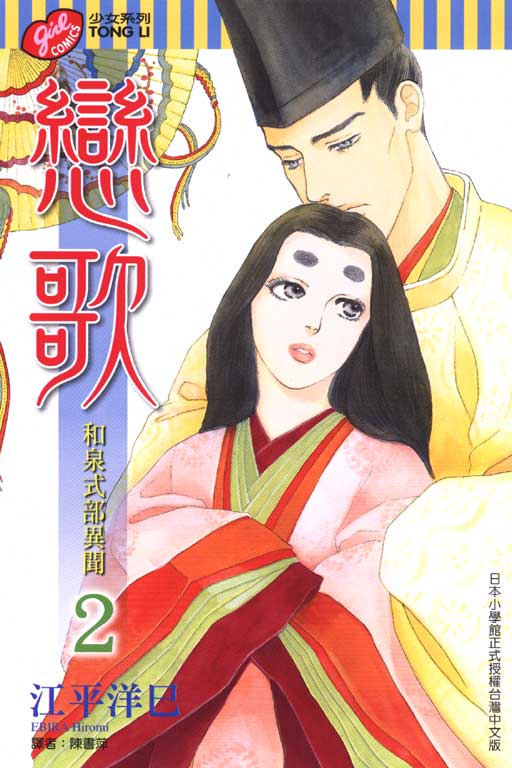

Even today, she is the subject of many romantic manga (Japanese comics) written for young women in Japan:

As well as stories about her life:

But Lady Izumi was also more than a femme fatale. She was obviously quick-witted, had many poetic talents, plus she was a loving mother (and grandmother), and a devout Buddhist who suffered many losses in her life. To me, she epitomized the bittersweet life of being a woman in Heian Period aristocratic society.

1 As Empress Shoshi was the second wife of Emperor Ichijō and a pawn in the power-struggles between two rival branches of the Fujiwara clan (the other faction tied to Emperor Ichijo’s first wife Empress Teishi), this was not a great position to be in, at least until Empress Shoshi successfully gave birth to a son.