Chariot racing stirred up both love and hate in ancient Rome

The fastest sport on two wheels thrilled fans in packed arenas across Roman lands, while the elite condemned—and exploited—the passions of the crowd.

Thundering hooves, spinning wheels, a cheering crowd: Envisioning an ancient Roman chariot race is easy, but many 21st-century notions of the sport come from the writings of the 19th. Adapted several times for the big screen (the 1959 film is perhaps the best known), the 1880 novel Ben-Hur climaxes with a thrilling chariot race. American author Lew Wallace meticulously researched classic texts to make his book as authentic as possible, but his passion for chariot racing comes shining through:

Can we accept the saying, then these latter days, so tame in pastime and dull in sports, have scarcely anything to compare to the spectacle . . . Let the reader try to fancy it; let him first look down upon the arena, and see it glistening . . . let him then, in this perfect field, see the chariots, light of wheel, very graceful, and ornate . . . let him see the drivers—in their right hands goads . . . in their left hands held in careful separation, and high, . . . the reins . . . let him see the fours, chosen for beauty as well as speed . . .

Wallace adored chariot racing, but ancient Rome’s relationship to it was more complicated. The spectacle, as described by Wallace centuries later, was indeed intoxicating, but some Roman elites looked upon racing with disapproval. These same elites funded the construction of massive venues for racing, such as the Circus Maximus in Rome and the Hippodrome in Constantinople. Chariot racing’s popularity only grew as the Roman Empire expanded. New stadiums were built in other cities, and racing became an obsession there.

Games for the gods

In the first century B.C., the poet Ovid, famous in his time for writing scandalous verse, used the racecourse as an arena for passion as well as sport. Book 3 of Ovid’s Amores (16 B.C.), describes an incident at the races, where a young woman is waiting for the race to start. The narrator explains to her his motive for being there: “You are looking at the race, I am looking at you; we’ll both see what delights us, and both feast our eyes.” Ovid’s verse, set in Rome’s Circus Maximus, compares the passions excited by racing with those aroused by the opposite sex. In Ovid’s time, competitive charioteering was popular and profane. (See a rare, ancient mosaic of a chariot race found in Cyprus.)

Chariot racing’s historic roots, however, tap deep into the sacred beliefs of ancient Greece, whose games—such as the Olympic and the Pythian events—were not considered entertainment. They were holy activities and part of solemn religious rites. The purpose of these events, which included chariot racing, was to please the gods, either through sacrifice or in presenting bodily skill as an offering in itself. Homer’s epic The Iliad features chariot races as part of the funeral games ordered by the mourning Achilles in honor of his fallen companion, Patroclus. The word “hippodrome” also comes from the Greek, with hippo meaning “horses” and dromos meaning“path.” (Delphi was home to the Pythian Games, sacred to Apollo.)

Games likewise formed an important religious role in the emerging power of Rome. Chariot racing was incorporated into the early Ludi Romani, the games held in honor of the chief Roman god, Jupiter Optimus Maximus. In 366 B.C. the Ludi Romani became an annual event, sponsored by the state. As Rome’s military influence grew, generals began dedicating portions of their war booty to sponsor chariot races and other games. Arguably, it is at this stage that the spirit of chariot racing began to evolve into entertainment. Sponsorship by generals boosted the popularity of racing and other sports, so by the first century B.C. the games were associated with mass culture, power, and populism.

By the mid-first century B.C., racing had become a major Roman spectacle. Julius Caesar commissioned a magnificent new hippodrome, the Circus Maximus, in the valley below Rome’s Palatine Hill, an area that had long been used to stage horse races. Built around 50 B.C., this venue featured a track measuring about 1,700 by 260 feet, 12 starting gates (carceres) for chariots, a decorated barrier (spina) dividing the track, turning posts (metae) at each end, and lap markers in the shape of eggs and dolphins. Each marker would be turned when a section of a race was completed. Caesar’s circus could seat as many as 150,000 spectators, but when the venue was later expanded by Rome’s emperors, it could hold as many as 250,000.

THE CHARIOT TRAP

One of Rome's violent founding myths, recounted by first-century historian Livy, centers on how Rome’s legendary founder, Romulus, came up with a plan to increase the city’s female population by abducting women from a neighboring tribe, the Sabines. Romulus invited the Sabine people to attend a festival, in which chariot racing would be part of the festivities. The lure worked, and dozens of women were seized by the Romans.

Team colors

Chariot racing was not the only athletic entertainment in ancient Rome. The venationes (killing of wild animals), gladiatorial fights, and mock naval battles were all popular attractions, for both the skill of the participants and the spectacle of the events. What seemed to set chariot racing apart from those other attractions was a strong sense of loyalty to a favorite team of charioteers. (DNA reveals far-off origins of ancient 'gladiators.')

Much like sports leagues today, Roman chariot racing had teams with legions of devoted fans. The four factions—Red (Russata), White (Albata), Blue (Venata), and Green (Prasina)—existed during the republic and continued well into the empire. Third-century A.D. writer Tertullian recorded that the rivalry between Whites and Reds was the oldest. Their supporters would reinforce the sense of enmity between the two by associating White with winter and Red with summer. Teams could also be associated with divinities: White with the wind god Zephyr and Red with the war god Mars.

Roman chariot races were thrilling and short, but occasionally brutal. The race would begin with the dropping of a white handkerchief (mappa). In a standard race at the Circus Maximus, each team could enter three chariots, so when the mappa fell to the ground, a total of 12 horse-drawn vehicles might shoot out from the traps (carceres) in clouds of dust. There were variations in the equine makeup of a chariot team, some featured as many as seven horses, some as few as two (the biga). The quadriga, composed of four horses, was the most common configuration.

RIDING HIGH

Junius Annius Bassus was made consul of the empire in A.D. 331. A scion of a powerful political family, Bassus commissioned a panel (above) for his opulent civil basilica on Rome’s Esquiline Hill. It depicts him in a two-horse chariot (biga) as part of the prerace procession, surrounded by charioteers of the Red, Blue, Green, and White factions. His association with chariot racing projected not only wealth and glamour but also strength and virility.

The aurigae, or drivers, would careen on their two-wheeled chariots to make the death-defying turn round the ends of the spina. The usual course was seven laps, run counterclock-wise around the arena. Races lasted anywhere between 10 and 12 minutes. As many as 24 races could be run in a day, to the delight of fans. Their devotion to their team could even lead to cheating: There are accounts of spectators trying to sabotage the race by throwing tablets studded with nails onto the track.

Drivers and horses

Charioteers and even their horses became superstars with devoted loyal followings. Perhaps the best known and wealthiest of his time was Scorpus, who drove for the Green faction in the first century A.D. Sources say he won more than 2,000 races before his death at age 27, most likely in one of the spectacular pileups that the Romans called naufragia, which means “shipwrecks.” A former slave, Scorpus purchased his freedom with his earnings.

When Scorpus died, the Roman poet Martial penned his eulogy:

Oh! sad misfortune! that you, Scorpus, should be cut off in the flower of your youth, and be called so prematurely to harness the dusky steeds of Pluto. The chariot race was always shortened by your rapid driving; but O why should your own race have been so speedily run?

Pliny the Elder documented the deep grief felt by fans at the deaths of their favorite drivers. In his Natural History, Pliny wrote how “at the funeral of Felix the charioteer of the Reds one of his backers threw himself upon the pyre—a pitiful story.”

Horses also gained fame and adoration. In addition to celebrating Scorpus, Martial mentions the horses: “I am that Martial known to all nations and people . . . I am not better known than the horse Andraemon.” Dedicated fans would know each horse’s lineage. The most successful would be honorably retired when the moment came, so that they could live out their last years in peace and procreate to continue their pedigree. Some even had funerary monuments dedicated to them, such as that raised to Spendusa:“[F]ast as the wind, incomparable in your life, you now . . . dwell in the realm of Lethe.”

THAT’S ENTERTAINMENT

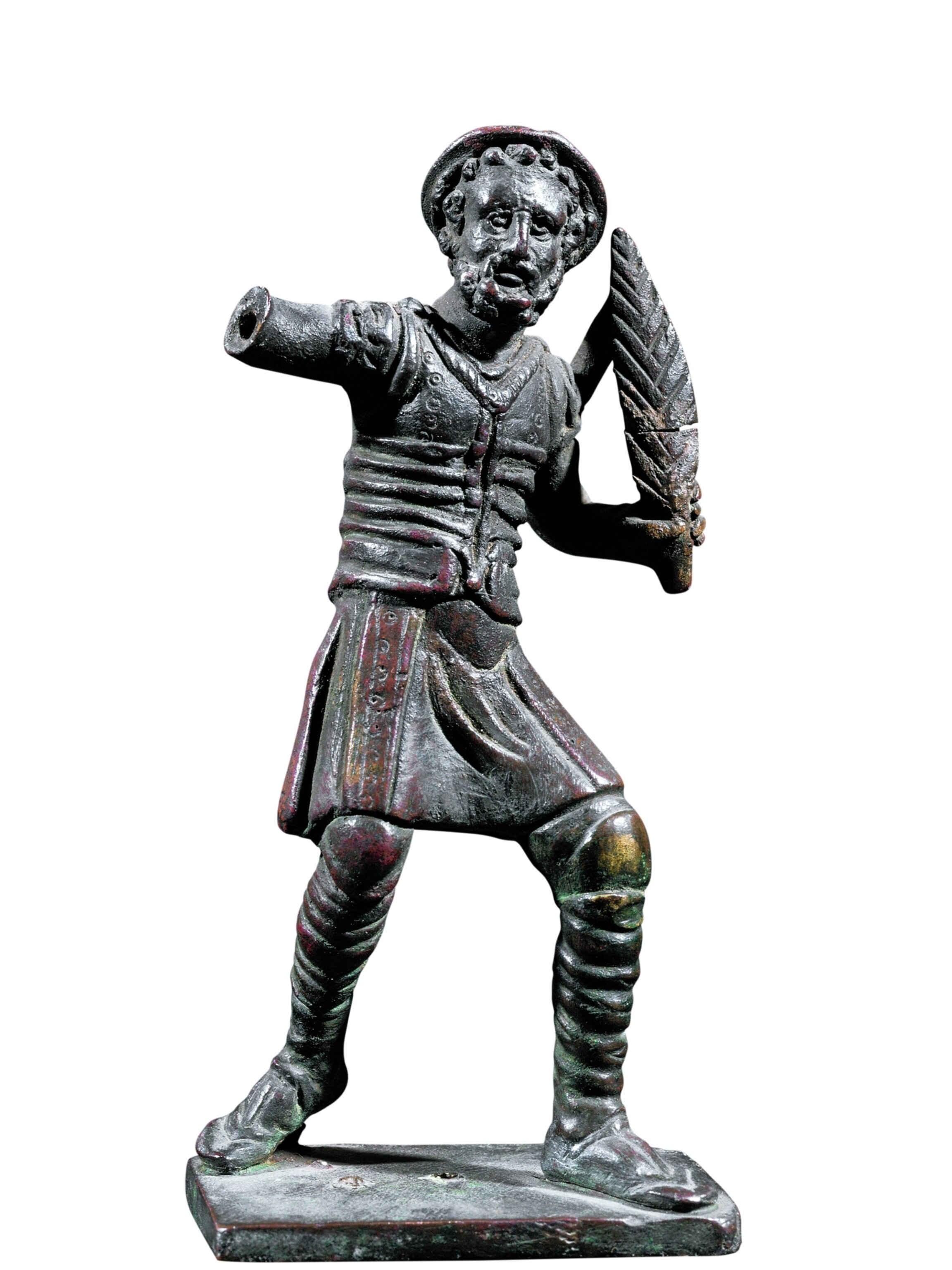

Keeping the crowds entertained between races was an important job, and talented groups of professionals were hired to do just that. These performers, called histrions, would act out mythological scenes to keep people in their seats. In early Roman history, they were associated with ritual dancers from neighboring Etruria, but by the time of imperial chariot racing, they added dancing and acting to their repertoire. While histrions performed in groups, the pantomimus (“imitator of everything”) performed alone accompanied by instruments. They used gestures and masks to portray a series of characters. For the most part the histrions and pantomimi were either enslaved or of low-born origins. They were, nevertheless, regarded as skillful professionals, and the best of them could keep the crowd engaged and excited. A few acquired fame and considerable wealth.

Bread and circuses

A great deal of money and power was at stake in chariot racing. Senior public figures pumped money into the games in the hope it would increase their political standing. A central figure in the booming business aspect of the races by the first century A.D. was the dominus factionum, the entrepreneur in charge of a faction. (200,000 miles of Roman roads provided the framework for empire.)

The huge sums of money could spark bitter, state-level disputes. In the early first century, a high-ranking official was accused of trying to delay payment of the cash prizes, which could range between 15,000 and 60,000 sesterces. His name was Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, whose son, Emperor Nero, would develop a singular passion for chariot racing and actually participate in races. On one occasion, Nero himself tried to pilot a chariot pulled by 10 horses. This was too much for him to handle. He was thrown, and severely injured, but managed to survive.

For all its popularity, chariot racing did have its critics. Long before Christian polemicists like Tertullian singled out the immorality of the racecourse, pre-Christian Romans expressed discomfort with the games in general. In a letter written in the early second century, Pliny the Younger writes of the fans at chariot races:

There might be some reason for their enthusiasm if it was the speed of the horses or the skill of the drivers that was the attraction, but it is the racing-colors which they favour . . . Such is the influence and authority vested in one cheap tunic.

For all the distaste they felt, influential Romans also knew that the races, and games in general, were interwoven into Roman state power. On taking the office of aedile in 69 B.C., the orator Cicero had to swear to uphold the games for the people of Rome. Later, in his treatise On Moral Duties (44 B.C.), however, he argued that the practice whereby rich rulers buy public favor through lavish entertainment is imprudent: “gratifying to boys, and weak women, and slaves, and to free men who bear the nearest resemblance to slaves.” (Cicero's beheading ushered in the beginnings of the Roman Empire.)

STAFF AT THE CIRCUS

The idea that the races, and games, were a tool for social control was most memorably expressed by the early second-century author Juvenal. In one of his satires, he writes about how easy it was for politicians to buy influence with voters, who“anxiously hope for just two things: bread and circuses.”

Christianity and chariots

As the Roman Empire grew larger, chariot racing expanded throughout its provinces. Hippodromes were built in the major urban centers across the empire, including Antioch and Constantinople (Turkey), Ceasarea (Israel), Alexandria and Oxyrhynchus (Egypt), Thugga (Tunisia), Toledo and Cordoba (Spain), Lyon (France), and Vienna (Austria). As part of his Romanizing program, the client king of Judaea, Herod the Great, had instituted chariot racing as part of formal games in 28 B.C. Sources record a hippodrome built in Jerusalem some time after, but its location has not yet been identified.

By the fourth century, the factional system of color-based racing teams was firmly established, especially in Constantinople, which had become the capital city of the Roman Empire in A.D. 330. Constantine the Great rebuilt the city’s hippodrome and expanded its capacity to seat as many as 100,000 people. The Circus Maximus was still bigger, but the Hippodrome became the center of life in the new Roman capital. The Reds and the Whites would eventually disappear, but the Blues and the Greens grew stronger and emerged as the leading factions.

Also by the fourth century, a tradition had established itself linking certain charioteers with sorcery. Historian Ammianus Marcellinus recounts the execution of a fourth-century charioteer in Rome for this crime, perhaps reflecting the widespread belief that charioteers lived beyond the bounds of respectable society. Chariot racing was both fantastically popular and morally suspect—negative associations that also fed into the growing Christian antipathy to the sport.

A day at the races

Among the cache of papyri found at the Egyptian city of Oxyrhynchus—about 100 miles southwest of present-day Cairo—is a program (left) of the planned entertainment for a day at the races. Written in Greek, the document dates to the sixth century, when racing was beginning to decline across the empire. Only six races were scheduled (larger hippodromes could schedule up to 24), and other entertainments were planned for in between events. The program is written in two hands, suggesting a process in which local officers approved the running order. The day’s events, as recorded on the papyrus: 1st chariot race; Procession; Singing rope-dancers; 2nd chariot race; The singing rope-dancers; 3rd chariot race; 4th chariot race; Mimes; 5th chariot race; Troupe of athletes; 6th chariot race. Farewell.

St. John Chrysostom became Archbishop of Constantinople in A.D. 398, fewer than 20 years after the Roman Empire adopted Christianity as its state religion. In a fiery homily, the furious archbishop reported that Christian believers had left the fold,“deserting us for the spectacle of horse racing.”

He ended with an ultimatum: Anyone attending the races would be excommunicated. His warnings were in vain. By the fifth century, chariot racing in Constantinople underwent an evolution: As Christianity stabilized, the controversies of the new state faith were absorbed into the local charioteering rivalries.

Historians differ on the extent to which Christianity drove the intense hostility between the Blue and the Greens in Constantinople. As a general rule the Blues were associated with the establishment and orthodox Christian beliefs, while the Greens styled themselves as closer to the people. It was in this setting that the so-called Nika riots engulfed Constantinople. Factional tension was intensified by the emperor Justinian I’s allegiance to the Blues, and the fact that his wife, Theodora, belonged to a family of circus performers, formerly Greens, who had switched their allegiance to the Blues.

Tension over taxation attached itself to the Green-Blue enmity, and in A.D. 532 Justinian had people from both factions killed. Greens and Blues found common cause, and they turned the exhortatory hippodrome cry of “Nika, Nika!—Win, Win!” against the emperor himself. As disorder spread, Theodora boldly took the initiative and sent in mercenaries to slaughter Greens and Blues indiscriminately. The Nika riots left as many as 30,000 dead and effectively broke the power of the factions. Amid religious tensions and civil war in the Byzantine Empire, the appetite for racing started to decline at the end of the sixth century.

In Rome, the last official race was held at the Circus Maximus in 549, in a city then under control of the Ostrogoths. Charioteering had run a long race, but the experiences of Rome’s racing fans are a foundation for the potent mix of camaraderie and tension experienced in stadiums all over the world today.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

Environment

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

History & Culture

- Meet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'iMeet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'i

- Hawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowersHawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowers

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

Science

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

Travel

- A slow journey around the islands of southern VietnamA slow journey around the islands of southern Vietnam

- Is it possible to climb Mount Everest responsibly?Is it possible to climb Mount Everest responsibly?

- 5 of Uganda’s most magnificent national parks

- Paid Content

5 of Uganda’s most magnificent national parks