Monday night's eruption on Iceland's Reykjanes Peninsula could mark the start of over a century of volcanic activity in the region, an American volcanologist who has visited the area multiple times said.

Ben Edwards, a professor of geosciences at Pennsylvania's Dickinson College who has traveled to the peninsula regularly since 2008, told Newsweek that the volcanic event "seems to be consistent with the start of a new set of 'fires' on the peninsula that could last intermittently for 100-plus years."

He cautioned that this "doesn't mean that there will be continuous eruptions" but that they could occur every few years on average.

"This is the edge of two tectonic plates, and so that is what is expected to happen here," Edwards said. "Having said that, though, this will be the first time in the history of those eruptions [that they will happen] with modern technology to monitor and better understand one of the most fundamental of geological processes—plate tectonic spreading."

This comes after a leading Icelandic volcanologist told Newsweek before the eruption that after a dormant period, the activity leading up to it could mark the start of a new episode of "rifting and volcanism" on the peninsula.

"We know that this is not the end of activity on the Reykjanes Peninsula," said Haraldur Sigurdsson, an emeritus professor of geophysics at the University of Rhode Island. Much of Iceland's infrastructure—including the capital, Reykjavík—is located in the region, he added.

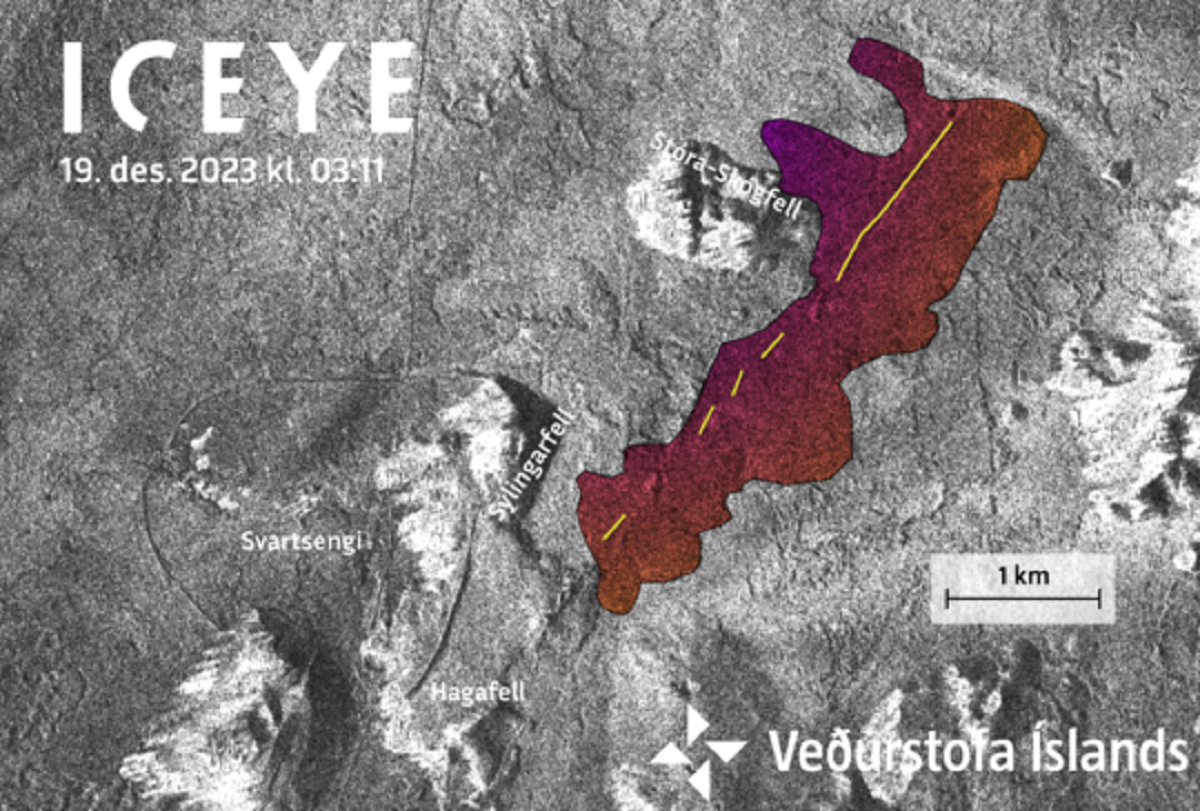

Monday's eruption saw lava fountains reach up to 650 feet in the air after emerging from a fissure to the northeast of the coastal fishing town of Grindavik, which was evacuated earlier and has been surrounded by earth walls to divert lava flows.

The lava emerged after a month and a half of anticipation, following a period of intense seismic activity in the region, which authorities said was due to magma propagating into the Earth's crust.

The fissure broke through in the middle of an underground vertical magma intrusion, around 9.3 miles long, that had formed in a weak point in the crust. It is thought to be connected to and fed by a horizontal reservoir of magma around 6 miles in diameter that has been pushing the ground up by around a centimeter (nearly half an inch) a day underneath Svartsengi, a nearby geothermal power plant.

On Tuesday evening, the Icelandic Meteorological Office said that while the eruption "continues to weaken," there is an increased likelihood of more vents opening up along the path of the vertical magma dike. The number of vents had fallen from five to three.

It also said the land around Svartsengi had sunk by 7 centimeters after rising by 35 centimeters since a magma tunnel was formed on November 10. But it was "too early to determine if magma will continue to accumulate" beneath the surface there, which could ratchet up the pressure again, the office said.

Edwards, who last traveled to the Reykjanes Peninsula in August, said before the seismic swarms that there "were no imminent signs of an eruption coming." But since the eruption of Fagrdalsfjall in the same region in 2021, "it has seemed likely that this was the start of another episode of historic eruptions on the peninsula" and "what is happening now is more expected than a surprise."

He said that while the ongoing eruption would likely keep most of the shallow magma under the peninsula focused on the vertical intrusion, there was "no reason" other eruption sites could not open up along it.

"There is a lot of magma in the crust right now, and we don't really know how erupting it to the surface may change the system pressure," Edwards continued. "Will magma stop coming up from depth or will that increase? Unfortunately [or] fortunately, once this eruption episode is done we'll know a lot more for the next one."

A sudden shift in the North American tectonic plate away from the Eurasian plate is thought to have allowed magma to suddenly push upward through a rift that runs between them under Iceland, creating the swell in the Earth's crust and the latest intrusion.

Sigurdsson previously said that rifting and associated volcanic activity in the region has historically been "very episodic," with periods of "intense" activity followed by 800 to 1,000 years of quiet. In the most recent quiet period, which experts believe may have ended with the eruption of Fagrdalsfjall, some of Iceland's important infrastructure has been built up on Reykjanes.

The lava from the current eruption has so far not moved toward Grindavik or the power plant at Svartsengi, which has also been protected by earth walls and channels. But there is no indication that new fissures or volcanoes could not crop up elsewhere in the future.

"Young lavas go right up to the southern and eastern edges of Reykjavik suburbs, so that is always on people's minds when something like this starts," Edwards said. "Much of the area around Grindavik is still mainly unoccupied, but every year I go I see a lot of new infrastructure—geothermal power, on-land fish farms, etcetera—because the high heat flow is great for geothermal energy."

Iceland draws much of its energy from geothermal power plants like the one at Svartsengi, so volcanic activity is a double-edged sword: It promotes the building of key infrastructure but also poses a threat to it. "You can't have one without the other," Edwards said.

Preventive measures such as earth walls and diversions can go a long way to protecting man-made structures, and eruptions like the latest one gave advanced warning through seismic activity—though "it is very expensive and stressful for people trying to get this done," he said.

A friend who works for Iceland GeoSurvey (ISOR), which provides geothermal energy, told him it has been scouting new sources of cold and hot water in case there were problems at Svartsengi. "Icelanders are used to thinking quickly to respond to disasters," he said.

Reached for comment on Wednesday, an ISOR spokesperson told Newsweek to contact Iceland's Department of Civil Protection and Emergency Management, which has not yet responded.

Sigurdsson suggested on Tuesday that the immediate threat to the peninsula had subsided and that the latest eruption could be over by the end of the month. He said the residents of Grindavik "should be allowed home for Christmas," though other experts said it was "too soon to say" how long that might last.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aleks Phillips is a Newsweek U.S. News Reporter based in London. His focus is on U.S. politics and the environment. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.