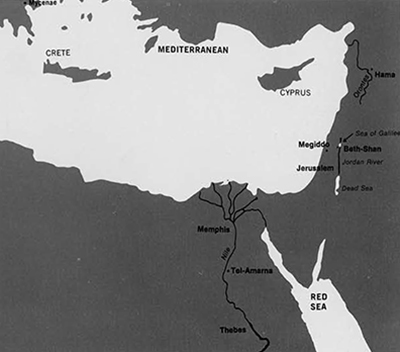

Among the Late Bronze materials from the University Museum’s excavation of biblical Beth Shan, 12 miles south of Lake Galilee, there are a number of stone knobs of varying sizes and shapes. Some are of marble; some of Egyptian alabaster, or calcite; some are of the local Beth Shan alabaster, or gypsum.

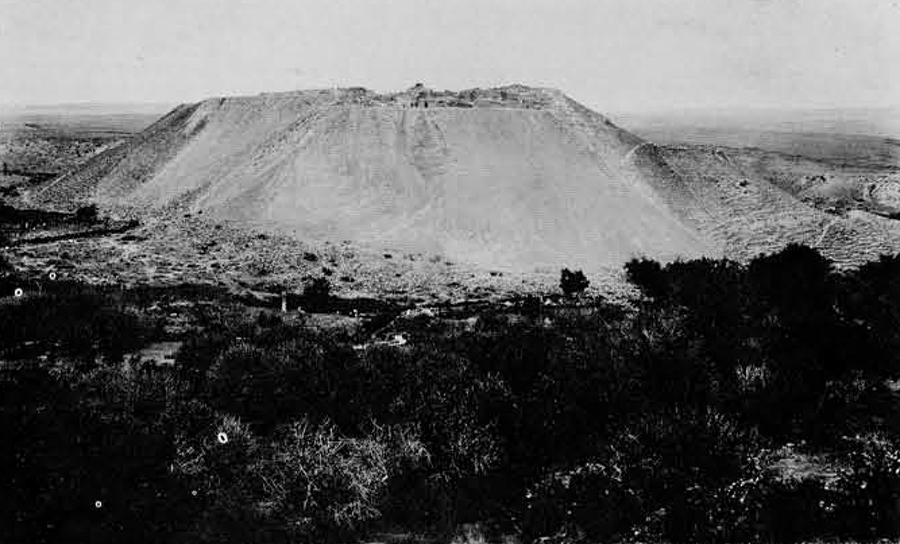

Among the Late Bronze materials from the University Museum’s excavation of biblical Beth Shan, 12 miles south of Lake Galilee, there are a number of stone knobs of varying sizes and shapes. Some are of marble; some of Egyptian alabaster, or calcite; some are of the local Beth Shan alabaster, or gypsum.

Last year when I began work on the publication of the Late Bronze Age at Beth Shan, I wondered what could ever be done with the knobs, of which there were registered about twenty. Most of those that had been kept had come to Philadelphia; apparently no one thought them worth retaining for Jerusalem. They are, in fact, the sort of residual material which occurs in every excavation. It should be published and, if possible, interpreted, but unimpressive objects of unknown use are all too easy to disregard. Yet things of this description can often, as in this case, produce information all out of proportion to their unassuming appearance. What, what, what were they?

We know that Beth Shan, in northern Palestine, was at this time one of the great strongholds from which Egypt’s Syro-Palestinian province was administered. During the reign of Ramesses III, just into the Iron Age and at most 200 years later than the earliest of the knobs, the Beth Shan garrison was commanded by one Ramesses Weser-kepesh, “Commander of Troops of the Lord of the Two Lands, Great Steward and Overseer of Foreign Countries and Fan-Bearer on the Right of the King,” obviously a very high official. On this basis alone, Beth Shan must have been a very important frontier post. In Early Iron Age level VI, a very impressive house of the type current in XIXth and XXth dynasty Egypt had been constructed by this official; in fact, it is inscriptions from its doorjambs that provide our information about him and much of the Egyptian activity in Palestine at this time.

Just before this, in the final stages of the Late Bronze Age, the city figures as the site of a dramatic Egyptian putdown of the Canaanites when Seti I, or one of his generals, on the 10th day of the 3rd month of the 1st summer of Seti’s reign (c. 1320 B.C.) led the army of Re (Many Braves) to Beth Shan to deal with the “wretched enemy” of Hamath and Pella, two other Palestinian towns which were trying to “liberate” Beth Shan from the Egyptians.

We know this from a beautifully carved basalt stela found in lower level V where it had fallen below a second stela, a rather bombastic one of Seti’s son, Ramesses II, which at least demonstrated much Egyptian interest in Beth Shan in the period between Seti and Ramesses III. In fact, though only a small fragment of any further stelae was recovered at the site, there were altogether in lower Level V, dating perhaps from 1,000 B.C., five stela bases in situ. The stelae which had stood on them must have been moved up to this Iron Age level from the Late Bronze Age strata in which they originally stood, suggesting both much activity on the part of the Egyptians and quite a lot of loyalty to them on the part of the citizenry of Beth Shan.

So it was no surprise to find a bronze trumpet among the Late Bronze Age materials. This, of course, found a comparison with contemporary copper and silver trumpets from the tomb of Tutankhamun. When I had read what Howard Carter had to say about these, I riffled through the remainder of his delightful volumes on the discovery of this tomb to see what other parallels might exist with objects from Late Bronze Age Beth Shan.

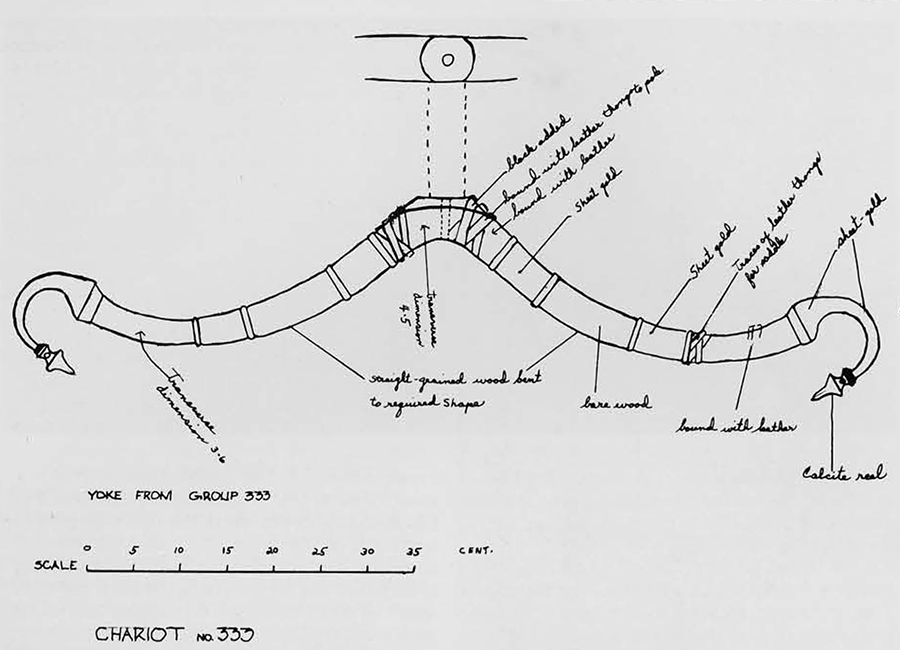

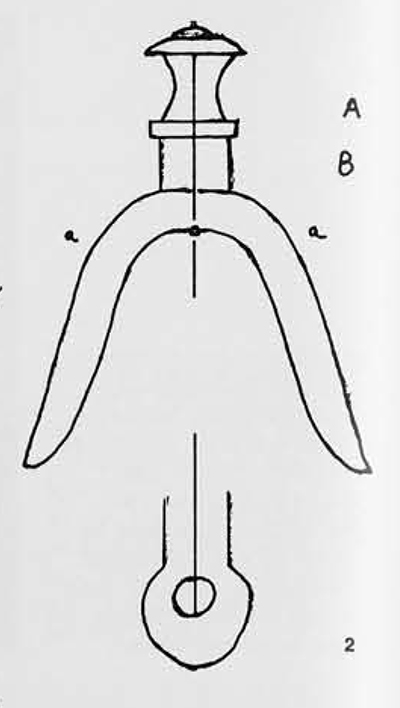

And there were the alabaster knobs! All types of them and no doubt about it. The smaller ones, 11/2″ high, looking like finials on Chippendale desks, were the really elegant terminals of the yokes of pharaoh’s state chariots—the (literally) gold-plated Cadillacs of the day. The larger knobs, 3″ high and about as much in diameter, looking like spools with swollen flanges, finished off the harness saddles put upon the horses’ withers. Who would ever have expected such unassuming knobs hitherto published, if at all, as sceptres, stoppers, staff heads and dagger pommels, to have had at once so exotic and so plebeian an application, or to prove the key to a pressing archaeological problem?

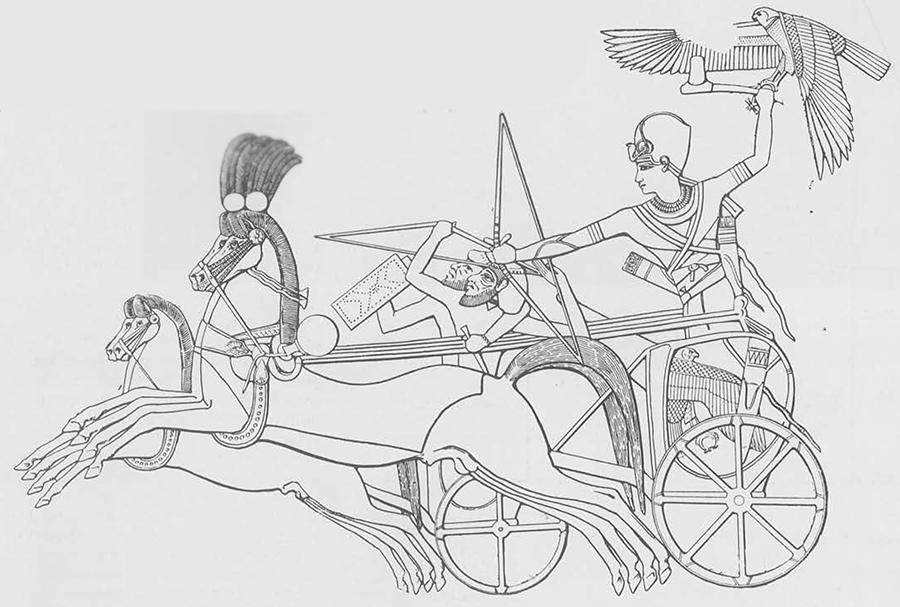

In Egypt, tombs and other monuments from the 16th century B.C. on produce an incredible number of chariot representations. On reliefs and paintings, chests and chairs, ivory boxes and other small objects: pharaoh and his nobles, fascinated with their speed and verve, stand braced with bow drawn on the lion which always so conveniently pursues them across the desert, or, in battle scenes, bowl triumphantly across a carpet of the dead and dying.

Yet without real roads, without springs, with bodies so light they could be carried on the shoulder of a man, with only tightly stretched leather thongs for flooring, chariots must have been incredibly hard to balance in and the famous flying gallop must have deposited many a dignitary in the ditch or on his head, as befell the Maher in the Anastasi papyrus dated to the reign of Ramesses II, c. 1304-1237 B.C. Somewhere in Syria, perhaps not far from Beth Shan, as the background described could very well have been the Wadi’Arunah, near Megiddo 12 miles to the west, this swift military courier finds that he is:

“. alone, there is no helper (?) with thee, no army behind thee. Thou findest no … to make for thee a way of crossing. Thou decidest (?) (the matter) by marching onward, though thou knowest not the road. Shuddering (?) seizes thee, (the hair] of thy head stands up M, thy soul is in thy hand, thy path is filled with boulders and pebbles, without a passable track (?), overgrown with reeds and brambles, briars (?) and wolf pad. The ravine is on one side of thee, the mountain rises (?) on the other. On thou goest jolting M, thy chariot on its side. Thou fearest to crush thy horse … The chariot is too heavy to bear the load .. . Thy heart is weary. . . .”

Scores of real chariots were also deposited with the grave furniture of those who could afford it. Yet astonishingly few of the actual vehicles have survived to our time. While the dry Egyptian climate has a very high preservation record, it has in this case been defeated by the inevitable tomb robber who breaks up and often burns the perishable materials he does not want in a rather silly attempt to cover the traces of his entrance.

Of complete chariots extant today, there are perhaps half a dozen from the tomb of Tutankhamun, still essentially unpublished though this work is now under way. These have wheels with six spokes and include two much-pictured state chariots with gold-covered gesso reliefs of battle scenes. There were also at least three lighter vehicles, or curricles, used for hunting or exercising. Nothing at all has been published on the curricles.

Two other Egyptian chariots are known; these come from the earlier part of the XVIIIth dynasty. One of them belonged to Yuya, the grandfather of Tutankhamun. It is, however, a life-size model made especially as tomb furniture. It is doubtful that it was ever used, even in the funeral procession, as its red leather tires are virgin. So its details may be open to some question.

The second early XVIIIth dynasty chariot, of unknown provenance, is now at the Museo egizio in Florence. It has wheels with four spokes, which seems to be the type of wheel in use when the Egyptians took over the entire idea of the chariot from the Canaanites, c. 1600 B.C.

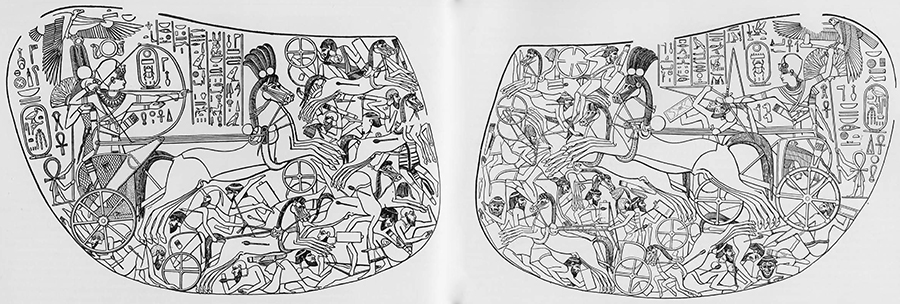

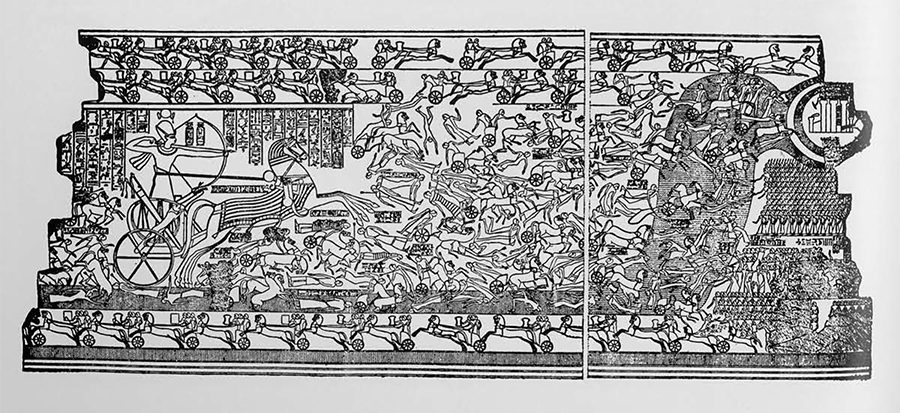

Then we have the body of the chariot of Tuthmosis IV, c. 1425-1417 B.C. Like Tutankhamun’s state chariots, it was originally covered in gold but robbers have left only the underlying gesso relief of a lively battle scene, naturally including chariots hurled as thick and fast into the fray as possible. In this relief, Tuthmosis IV’s chariot has an Egyptian innovation, wheels with eight spokes (later discarded in favor of the six-spoke wheel) while the enemies’ chariots have the old four-spoke type. The weapons of the Egyptian chariotry at this time consisted of bow and arrow and pharaoh’s chariot is equipped with triangular bow case and quiver; later, javelins were added to the weapons of the mobile corps and a pouch for them is seen on the later reliefs of Ramesses II from the Ramesseum. Normally Egyptian chariots had a crew of two, the driver, ktn, and the archer, smn.

A few complete wheels are also known, notably the six-spoke wheels from the chariot of Amenophis Ill, c. 1417-1379 B.C. These were found in the wreckage of his tomb in the Valley of the Kings; they are absolutely beautiful examples of wood working.

While chariots are numerous on the walls of the Egyptian tombs, it is difficult to identify the yoke terminals and saddle bosses in many of these representations, not surprisingly in view of the small size of these stone knobs and the less than perfect surface of the surviving walls. One relief which does show them quite clearly comes from the tomb of Pentu at Amarna. These chariots of c. 1360 B.C., as well as Tutankhamun’s, would be roughly coeval with the earliest of the Beth Shan knobs.

The Amarna representation is part of a much larger relief depicting Akhenaten’s visit to the Temple of the Aten. In the portion shown here five chariots are drawn up, the one in the lowest register belonging to pharaoh, while those in the two upper registers, though lacking the bow case and quiver of the military vehicle, at least belong to ordinary mortals and must more-or-less parallel those from which the Beth Shan fittings came.

Actually, the royal chariot here differs only in the headdress of its steeds and in the presence of a large, unornamented disc attached to the harness at the base of the horses’ manes. This disc is confused with or obscures the saddle bosses in many of the representations of the royal chariot. The objects found with Tutankhamun make it quite clear, however, that this disc does not represent a saddle boss. Fittings for the pole of one of his state chariots included a six-inch bas-relief disc of the falcon Horus in gold leaf; a representation from the Ramesseum of Ramesses II at the battle of Kadesh bears a gold disc with a relief of Ramesses making a sacrifice.

In the Amarna relief, the golden disc very nearly rests on the stone saddle boss, of which only the upper flange is visible. This, in turn, almost rests on the lozenge-shaped terminal of the yoke, which curves around into its position here, Egyptian perspective being what it was. Yoke terminals and saddle bosses are quite visible on the other chariots in this Amarna group. On some other reliefs, the saddle boss seems to be drawn out to look like a tiny papyrus column. This may represent a later type of boss, not yet identified among the archaeological materials, or it may simply be artistic license.

How large a chariot corps at Beth Shan is represented by the score of fitments found at this site is an interesting question and one that can be answered only in conjecture. If we equate Seti’s arrival with the 5,000-man division of Re with the 5,000-man, 50-chariot expeditionary force Rib Addi of Byblos asked pharoah to send during the Amarna period, we might take 50 chariots as appearing with Seti. This would problably have been the maximum stationed at Beth Shan, even though the knobs run through several later levels.

As the wealthiest nation of the ancient world, Egypt was essentially mass producing chariots during the Empire. There were chariot repair shops at strategic sites in Syria while mobile repair shops travelled with the army. This government production of material doubtless led to much standardization which could be archaeologically very useful. As several of the stone fittings from Beth Shan are of the unmistakable local gypsum, it is perhaps not unreasonable to suggest that one of the provincial repair shops was located here. It was to an establishment of this sort (at Jaffa, due west of Jerusalem) that the Maher took his smashed-up chariot:

“. . . Thou makest thy way into the armoury, workshops surround thee; smiths and leather workers are all about thee. They do all that thou wishest. They attend to thy chariot, so that it may cease from lying idle. Thy pole is newly shaped (?), its … are adjusted. They give leather coverings (?) to thy collar-piece (?)…. They supply thy yoke. They adjust thy … (worked) with the chisel (?) to (?) the

. They give a … (of metal) to thy whip; they fasten (to) it lashes. Forth thou west quickly to fight on the open field, to accomplish the deeds of the brave.”

At the period in human history which we are considering, the chariot—which is to say any type of wheeled vehicle whatsoever—was absolutely new in Egypt. It was not a variation on an earlier prototype or model but something which had never before existed at all in this area, This situation is difficult for us to comprehend today and the chariot’s effect on the Egyptians and their attitude to it is therefore also difficult for our technologically blase minds to encompass.

A new and really very complex mechanism was here introduced into a world of otherwise very simple ways of doing things. The chariot increased human speed, size, personality ratios, striking power in war and game, to say nothing of expanding amor propre in ways still to be found among the owners of fast sports cars, motorcycles and leather jackets, despite their familiarity with advanced technology.

While the chariot was new in Egypt in the Late Bronze Age, it had existed in one form or another in Mesopotamia and perhaps the Caucasus for two millennia. We know it had reached the middle Euphrates by c. 1850 B.C. But then? Presumably it did not diffuse to Palestine till the first half of the second millennium B.C. nor to Egypt till the second half of the second millennium. Just why it reached Egypt so late is an interesting point. Because Egypt was geographically so far from the chariot’s point of origin? Or because, with a highway such as the Nile, the chariot was of limited use in Egypt until the conquests of Empire brought its potentialities for warfare into focus? Chariots must have been known nearly 500 years earlier to any Egyptian visiting Retenu, as Syro-Palestine was at that time known.

Since nearly all of the elements of the chariot are of wood or leather, the case for its introduction into both Canaan and Egypt has to date rested on inscriptions, paintings and reliefs of various sorts, horse and/or chariot burials, plus the wheels of model chariot offerings, usually made of pottery. These are all good positive evidence, saying that the chariot was there. But chariots may have been present when no representations, burials or mention in literature was made of them.

Small stone fittings like those identified at Beth Shan are therefore likely to extend considerably our information on the presence of the chariot. Admittedly they too are not positive evidence but they should multiply the potentialities for obtaining it, as every one of these vehicles had two yoke termini and two saddle bosses, and chariots seem to have been fairly thick upon the ground once they did reach the Near East—at least assuming pharaoh told the truth about his conquests.

Tuthmosis III lists “one chariot wrought of gold belonging to the prince of Megiddo” and 892 chariots belonging to the prince’s “wretched army” as captured at the battle of Megiddo in 1479 B.C. In the aftermath of this encounter the Egyptians also collected 2,041 mares, 191 female colts, 6 stallions and an indecipherable number of male colts as further booty. Tuthmosis’ son, Amenophis II, lists 550 maryannu (or Syrian charioteers), 820 horses and 730 chariots as captured on the Asiatic campaign of his 7th year, c. 1443 B.C. Only two years later, in his 9th year, Amenophis tells us that he returned from Syro-Palestine with 60 chariots of gold and silver and 1,032 of painted wood.

Because of the imperishability of stone and the distinctive shape involved in the yoke terminals and saddle bosses, we should be able, in part at least, to deduce the presence of chariotry wherever it may occur on the clue of even a small fragment of one of these knobs. Presumably, when the Egyptians first adopted the chariot, they copied all parts of the prototype so exactly that fittings of the type described here should identify a chariot for some time both before and after the time of Tutankhamun. Even one of the Egyptian words for chariot, mrkbt, is a loan word from the Semitic, narkabutu. From this beginning, it will probably be possible to work out a typology for earlier and later examples of the knobs.

The archaeological bridge here constructed can be still further extended by the addition of the metal fittings with which the larger knobs, or harness bosses, are themselves ornamented and attached. On Tutankhamun’s chariot, these consist of red gold and faience rosettes fixed on the stone boss by a bronze nail, its head covered in gold leaf. The nail holds the entire knob complex on the wooden saddle. In the military chariots used at Beth Shan both rosette (if any) and pin must have been of bronze.

No suitable rosettes of this material occur among the Beth Shan fittings, but there are a number of large, bronze nails in the collection. These have always been puzzling as they do not occur in significant quantity for constructional purposes and, in any case, would have been quite extravagant for this use. A number, though they have lost through corrosion much of the 7″ length.which would have been required to do the job as described, do have heads about the right size-3/4″ in diameter. Further, the upper surfaces of several of the Beth Shan saddle bosses have marks of wear which fit the nail heads (left rear on photo 4, page 33). At Beth Shan these nails occur in the Iron Age as well as the Bronze Age levels, though the stone knobs do not, giving an example of the type of extension just noted.

At other sites the rosettes may be found in close association with the nails and saddle bosses, as well as with other pieces of chariot fittings still to be identified. Scholarship, if you like; detective work, if you prefer this term; this is an example of ordinary archaeological method applied specifically to the chariot: of seeing darkly, then “face to face,” when enough comparative material is available. It underscores once more the importance of the unimportant. The small stone knobs from Tutankhamun’s chariots prove every bit as valuable as the glamorous gold masks for which his burial is known.