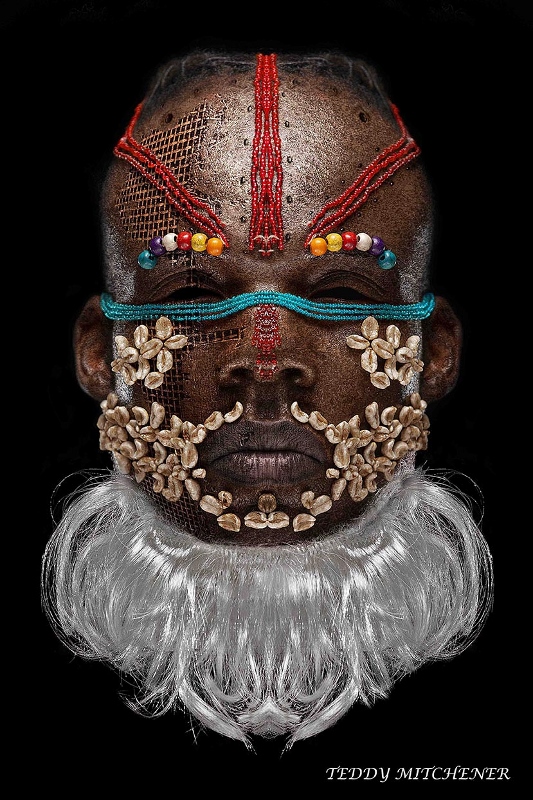

Above: Teddy Mitchener with Sharon his wife as a model for a mask. Copyright Sharon and Teddy Mitchener

Published: The East African Nation magazine February 2020

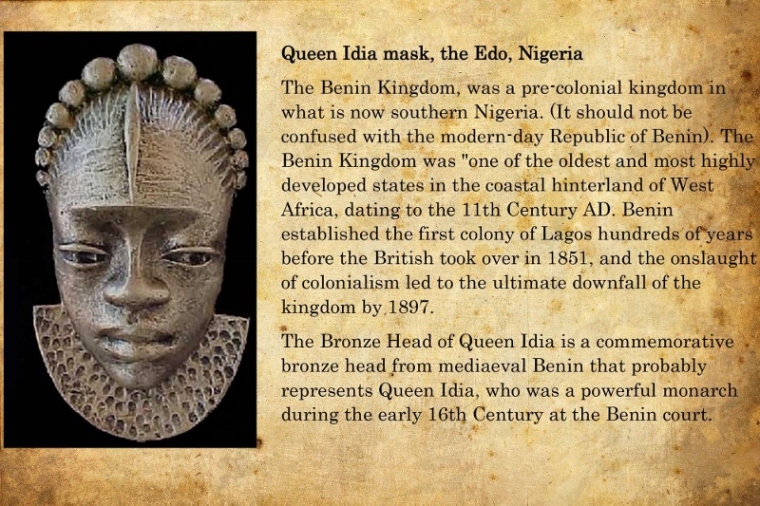

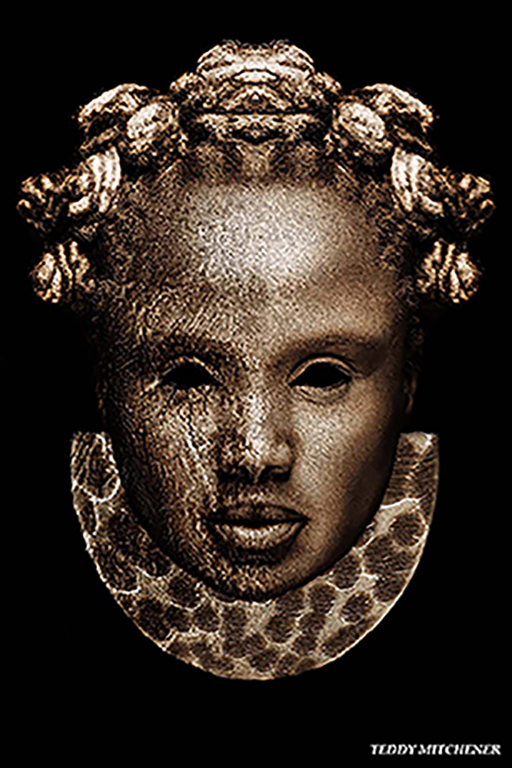

I was at the Nairobi Gallery that houses part of the late Joseph Murumbi’s (Kenya’s first foreign affairs minister) amazing art collection from all over Africa. On that day l was staring at a poster of a singularly beautiful mask of a powerful queen from the Benin Empire of the 16th century. It was of Queen Mother Idia done in ivory and iron inlay.

And it’s housed not in Africa but at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in the US.

This stunning mask including thousands of others dating between the 16th and 17th centuries were looted from the ancient Kingdom of Benin in southern Nigeria. Termed as the Benin Bronzes, they are cited as great works of art and metal casting, and were snapped up by Europeans (like Picasso) and the museums.

It took one incident to trigger the looting that destroyed the great kingdom. In 1897, a British official was sent to ask the oba (king) to stop interfering with British trade. The oba could not see him because of a religious festival. The British official went against orders of both the oba and the colonial administrators and was killed. The British retaliated and took the kingdom in a violent raid on 18th February 1897.

Contemporary Times

A few days later the French Cultural Centre in Nairobi announced an exhibition of African masks from around the continent. In my mind’s eye, l pictured some of the Benin Bronzes.

Instead l was staring at posters on the wall to my great annoyance having had to deal with Nairobi’s traffic to be on time for a presentation by Teddy Mitchener. Also with a name like that l was expecting a white guy like a bespectacled university don.

Instead Teddy Mitchener turned out to be a black guy – an African American – like a teddy, dressed in shorts and T-shirt and a baseball cap holding paint brushes working on a man reclining on a chair.

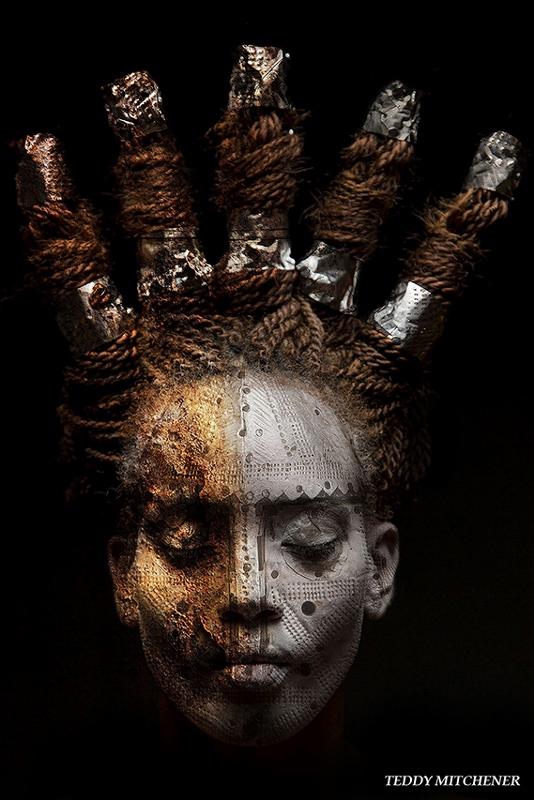

He was painting a Benin Bronze mask on the man.

Fascinated by Masks

“I grew up in Washington DC and Brooklyn around family and friends who had African art in their homes,” he narrates in his American drawl.

“It was the masks that intrigued me,” he continues. “I was a child and l was asking myself if it was someone’s face that was actually carved?”

Mitchener’s father saw the artist in his son – but of a different sort. A musician.

“My father was big in music and had various hobbies like photography. He had a regular blue-collar job but we were around each other a lot, celebrating every birthday…l mean l come from a big family.

Convinced his son had the talent to make it big in music, he sent the teenager with his mother to the prestigious Duke Ellington School of Arts in Washington DC where the likes of the famous comedian Dave Chappelle graduated from.

To cut a long story short Teddy missed being enrolled for music because he was late for enrolment and also could not ‘read’ music although he played great by the ear. Not accepting defeat, his father personally took his son to the school.

“He’s an artist,” said my Dad.

It was like a light bulb that went on. “Well take him to the art department,” they replied.

“I was given a paper and pencils to sketch the man on a chair. When l finished they were amazed. I was in.”

Teddy graduated in 1992 in visual arts. But while in school one African-American teacher fascinated him. A Dr Todd who could trace her lineage to Nigeria. Everybody wanted to be in her class.

“Africa was always in my heart but not a reality…you know of it like you hear of so many places … like Hollywood. And Dr Todd said, ‘That place (Africa) really does exist.’”

A Meeting in the Bahamas

“I had to get a job after school. My family could not afford college and l never got a scholarship.”

Teddy got a job as a train technician making a lot of money and travelling with the job but the love of art stayed. “I went to beautiful places and always said ‘when l return I’ll paint…that never happened because of time. So l started carrying my camera.”

In 2006 on a break in the Bahamas as fate would have it, he met Sharon Mugambi, the Kenyan living in the US who was also taking a break between jobs in the banking world. They dated and after her two-year contact with the World Bank ended, “I felt it was time to come back home. I’d been away for ten years,” tells Sharon.

She relocated to Kenya with Teddy and they married in the Mara in 2008.

New Beginning

“Ever since my second grade, l knew l was going to be an artist,” states Teddy.

It was in Africa that he honed his skills. The two with no background in the art world in Kenya had to knock on many doors before Teddy was noticed as a photographer of note.

“We had to create a space for ourselves and people did not want to share information,” recalls Sharon.

“So we created a digital magazine to showcase photography that seeks to capture and amplify the voice of the African photographer, behind the lens telling their own story.”

It’s called African Photo Magazine and can be viewed on a platform the couple created for their other art projects, http://www.TheImageFoundry.org.

The Journey to the Mask

“I wanted to do a story about an original Black Panther for the magazine,” tells Sharon who acknowledges she’s a history buff.

The Black Panther Party was the militant arm of the American civil rights movement that began in the 1950s up to the 1970s. Alongside Martin Luther King’s movement and the Nation of Islam Movement of Malcolm X, the Black Panthers fought for equal rights in a colour-segregated America.

They had heard of an original Black Panther, Pete o’Neal who has been in self-exile in Tanzania since 1963 to escape life in prison, granted a permanent refugee status by the late founding president of Tanzania, Mwalimu Nyerere.

“We never got to interview him in the end, but his wife Charlotte who was also in the civil rights movement probably felt sorry for us and took us to lunch at the Arusha Cultural Heritage Centre,” continues Sharon.

“The minute we entered, l was overwhelmed. There were hundreds of African masks. I was back to being a kid,” tells Teddy.

Charlotte introduced them to the owner Saifuddin Khanbhai who took them around the gallery.

This time the interview was on Saifuddin.

“It was about his love for African art, the culture and understanding and he wanted to preserve because the old artisans are dying and there’s no one to replace them. The youngsters are moving out of the villages and the internet is taking over everything.

“And that sparked in my mind. Like no one is going to preserve the heritage of the masks and sculptures. I thought about that all the way from Arusha to Namanga border talking about it with Sharon.

“When l talk to people about the arts l start to see visions. I’m driving and l’m seeing Mount Meru and l begin to see the masks and the feeling that they are not being made anymore…like the Benin Kingdom. The connection of the mask began to deteriorate.”

“And that’s pretty much how this concept came about.

“The work of this concept is to preserve what we can in the arts and culture.”

The Making of the Mask

“When l saw these masks the first time as a kid, it was the question … where did this mask come from? It had to come from a person.

“So it’s like when you paint a landscape. You have to look at it and understand it. Then you can begin to fantasise but it had to come from someone, somewhere the very first time it was made.

“And l said to myself, l’m going to make that mask that the artisan made of probably a person.

“I paint the mask on a person and bring it to life but also show one part of the mask deteriorating away to show the fact that culture is not being taken care of or that it has been lost by many things like the slave trade, colonial rule and the march of time…the assimilation of tribes and wars.”

“We pick a kingdom or tribe that has disappeared or is on the verge of,” adds Sharon. “I do the research.

Once the mask has been painted on with half a side deteriorated, Teddy shoots the model to preserve the ‘animated’ mask in digital form including selling some of the stellar kind.

And it was all due to AKKA Project that with his Disappearing Africa concept, Teddy has been invited to international art fairs. In 2019, he’s exhibited in Dubai with AKKA Project at the Gulf Photo Plus and in Venice and this year AKKA Project presented Teddy’s works to Photo Basel, and he has been shortlisted for the Photo Basel in Switzerland – and this time with the real masks alongside the photography prints, besides being commissioned around the world on photography assignments.

There are two things that stand out – identity and a strong background in the visual arts.

“If you don’t know where you come from, you have no distinct identity,” states Sharon.

“My art comes from a strong training in the visual arts that dealt with everything from sculpting to photography,” states Teddy.

“In Kenya art instruction still lags behind global practices. It’s primarily fine art, drawing and painting and not other new visual and applied art forms like photography and film, animation, conceptual art and so forth. This needs to change,” states Sharon.

end