La Perruche et la Sirène, 1952

Wheelchair-bound and afflicted with illness, it is extraordinary that the last decade of Henri Matisse’s life was one of such creative vitality. The artist, widely regarded as the leading colourist of the 20th century, exchanged the pallette and the brush during this period for a more radical choice of medium: paper cut-outs. Brimming with an exuberance of colour, shape and contrast, they were initially dismissed by critics as the senile exploits of a faded talent. To Matisse, however, the creations spawned an artistic rebirth – he called it ‘une seconde vie’ – and one to which the exhibition at London’s Tate Modern pays an exceptional tribute.

Polinesia, The Sky, 1947

The co-curator Nicholas Cullinan is not exaggerating when he calls the collection a ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ opportunity. It is rare to see the oeuvre of such a distinguished artist presented in its entirety, and not scattered incoherently in museums across the globe. The exhibition thus succeeds in presenting us with the gradual blossoming of these 130 cut-outs, and this is particularly enlightening. Matisse had long used paper shapes in order to formulate the arrangement of objects in his paintings, until they become an art-form in themselves: his vision quickly widened from small depictions of birds and flowers to more abstract, room-size canvases.

‘It is no longer the brush that slips and slides over the canvas, it is the scissors that cut into the paper and into the colour,’ said Matisse. ‘The contour of the figure springs from the discovery of the scissors that give it the movement of circulating life. This tool doesn’t modulate, it doesn’t brush on, but it incises in…’. Indeed, there is a strong inventiveness behind the inherent simplicity of these creations. Made out of just paper, scissors and pins, the works pulsate with a striking energy. The raw assortment of forms, edges and layers dance around the canvas in a waltz of colour. Matisse called it ‘drawing with scissors’, and one really senses his meaning when he described the process as ‘the graphic linear equivalent to the sensation of flight’.

The Snail, 1953

What I found most remarkable about the cut-outs is their multifariousness, both in terms of their individual production and potential. Oceania, The Sky, for instance, started with a small swallow cut out of writing paper stuck on the wall to cover a stain. Over time, Matisse built an ocean of fishes, coral and leaves in dreamlike suspension across the four walls of his flat. By contrast, in The Snail, he talks about an ‘abstraction rooted in reality’ as the shapes spiral outwards and away from the more lucid representations of his other designs.

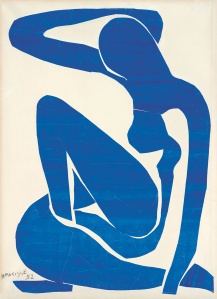

Blue Nude, 1952

Moreover, the Blue Nudes are perfect examples of the brilliance of Matisse’s eye for sculpture. Out of one single cutting movement, the artist takes a gouache-coated sheet of paper and brings to life a figure that undulates with the form and depth. It is notable that Matisse’s assistant Lydia Delectorskya described his processes in this way: ‘modelling like a clay sculpture: sometimes adding, something removing’. Nevertheless, each work lives and breathes in its own constructed dimension.

Matisse’s cut-outs are both vigorous and invogorating, inspired and inspiring, rich and enriching: a complete ‘one-off’ in the world of art, I have never witnessed anything remotely similar, either in terms of their impact or style. The artist claimed: ‘By creating these coloured paper cut-outs, it seems to me that I am happily anticipating things to come… But I know that it will only be much later that people will realise to what extent the work I am doing today is in step with the future’. It is fortunate not only that the exhibition celebrates this foresight, but that it does so in excess of all expectations.