Google Keith Haring and unlike fellow artists – Picasso, say, or Tracey Emin – you are as likely to find adverts as art. The ads suggest a sweatshirt from Abercrombie & Fitch featuring Haring’s artwork on the front for £60. A ring from Pandora with Haring’s dancing figures around the design for £125. Or a Uniqlo T-shirt, with two figures and a heart, for £14.90.

This is only a fraction of the items you can now buy displaying Haring’s artwork. The Keith Haring Foundation – the organisation responsible for his imagery since his death in 1990 – has partnered with a plethora of brands in recent months including H&M, Primark and Bershka, collaborations that follow its partnership with Uniqlo, which began in 2003. More than 30 years after his death, Haring’s crawling babies, barking dogs and dancing figures are ubiquitous.

Commercial value has long been a central tenet of Haring’s work. But are the sheer number of these new collaborations taking things too far, and compromising his legacy? Has his art been reduced to glorified logos? Have we reached peak Haring?

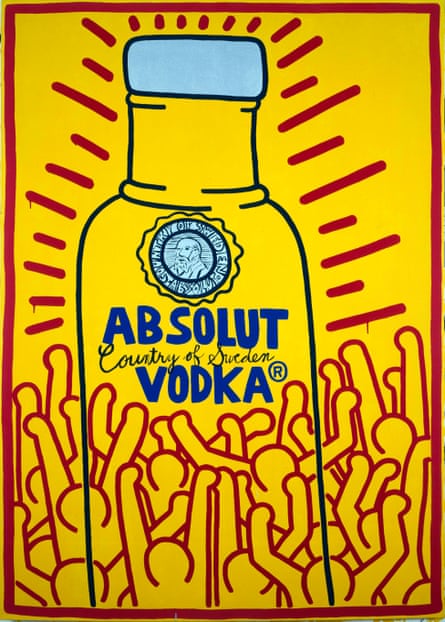

Haring was born in Pennsylvania and moved to New York to study art in 1978. Two years later, he began his subway drawings; the artist and his work became a familiar sight to commuters in the city. His fame grew during the decade – he was the subject of 40 articles in 1986, appeared in more than 50 solo exhibitions in his lifetime and created more than 50 public artworks. In his own lifetime, Haring had few qualms about commercial work. He worked with Absolut, Fiorucci and Swatch, although he also turned down some brands including deals with Kraft cheese and Dodge trucks. Crucially, in 1986 he opened Pop Shop, a store on Lafayette Street in New York, and sold T-shirts, toys, posters and badges for affordable prices.

Haring died of an Aids-related illness at the age of 31, but he left behind a significant body of work, and a life that made him a hero to many. He campaigned against racism, drug abuse (see his famous Crack Is Wack mural) and for the Aids organisation Act Up. He set up his foundation in 1989 to provide grants for Aids organisations and those working with disadvantaged children. The collaborations continue to generate revenue for those causes; last year, the foundation issued grants valued between $7m and $8m.

Some collaborations have nevertheless seen pushback from fans. In October, PinkNews ran an article highlighting responses to the most recent of them on social media. “Keith Haring is collaborating with Pandora, Primark, Casetify … what’s going on?” wrote one Twitter user, while others complained that Haring’s sexuality had been removed from the publicity around the Pandora collection. “Straight brands yet again appropriating and disrespecting the work of my communities’ artists, to flog a few earrings. Absolutely enraged,” was one comment.

Gil Vazquez, executive director of the foundation, is well aware of such criticisms. “We are often accused of not highlighting Keith’s fight against HIV in our licensing programme and it is often viewed as erasure of not only his struggle, but the struggle of the many that fought and died,” he says in an email. “It is a reality that we, the Haring Foundation, do not shy away from.” He adds that, as these are commercial projects, they come with different concerns: “We don’t think it is fair to force a brand to tell a story that doesn’t make sense for them. That being said, we’d love an opportunity to work with a brand that does want to tell a story about the HIV/Aids struggle in the 80s and 90s using Haring imagery.”

The ability to buy Haring for accessible prices is, Vazquez argues, a crucial part of staying true to the artist’s legacy. The foundation partners with Artestar, the company that acts as intermediary between artists and brands, on these collaborations (Artestar also handles artists including Jean-Michel Basquiat, Herb Ritts and Mickalene Thomas), and focuses on affordable brands. “Fast fashion gets a bad rap at times because of ecological concerns but, for us, it’s thinking about access,” says Vazquez.

Philippa Grogan, a sustainability consultant for Eco-Age, says she understands that these collaborations are in line with Haring’s thinking – “They’re appealing to the masses, just like he wanted” – but the bottom line remains that all fast fashion has a negative impact on the environment. “When brands release new collections, they’re contributing to the growth, [not] decoupling fashion from overconsumption,” she says.

Grogan adds that the foundation’s commitment to children’s charities could be undermined by working with fast-fashion firms. “I know for a fact that some of these brands can’t guarantee supply chains free from child labour,” she says. The foundation responds to this by saying every licensing agreement stipulates that a brand guarantees products made through the collaboration will not be made in a place that uses inhumane working conditions, child labour or forced labour.

Haring’s embrace of commerce came a long time before we started thinking about the human and environmental impact of what we were buying. He was partly inspired by Andy Warhol, a giant of art in his era, and a child of postwar consumerism. While Haring’s ethics weren’t questioned, there was criticism and dismissal from the art world. Robert Hughes called him “Keith Boring” and described his work as “amusingly facile”.

after newsletter promotion

Darren Pih, who curated Tate Liverpool’s Haring retrospective in 2019, says it is easy to dismiss Haring as purely commercial. But, he argues, his work is savvier than that, partly because of his commitment to activism. “His work had two edges,” says Pih. “He was critical of the market and capitalism and inequality. But also, for things like the Pop Shop, you can see he saw it as a way of reaching a wider audience.”

The products sold in Pop Shop often spoke to causes close to his heart; they featured slogans for Act Up or anti-apartheid messages. Emily Dinsdale, art writer at Dazed, says this is crucial. “He wasn’t precious about the commercialisation of his work, he cared more about raising the public consciousness,” she says. “In a sense, you could describe his work as propaganda for compassion and equality.” Harrison Tenzer, the head of digital strategy for Auctions, Modern & Contemporary Art (Americas) at Sothebys, worked on the Dear Keith auction of the artist’s personal collection in 2020. He says the way Haring lived his life resonates within his legacy. “His role as an activist is probably the strongest element of his lived experience. It adds to the cachet, for lack of a better term, around his artwork, because his art is very authentic to him and his vision, and he feels like an artist who really lived within his own morality.”

If critics were sniffy during his lifetime, Haring has – posthumously, at least – had the last laugh. Such is the demand for his artwork that a baby he drew on the wall of his bedroom in his childhood home was sold in September, an act that Guardian art critic Jonathan Jones called “brutal”, thanks to it being “ripped from its tender, intimate and original context to become an art world commodity”. Such extremes make sense when you discover that, in 2017, a Haring canvas was sold for £5m at Sotheby’s.

Tenzer says that the market has grown over the last five years, as collectors have digested Haring and his contemporaries. “There is a growing interest in that era and generation of New York artists. It straddles so many different realms – street art, being ready-to wear-merchandise as well as having a fine art practice – [and] I think this generation of collectors is very comfortable with all of that.”

Ultimately, it is perhaps the simplicity of Haring’s work that allows it to exist in multiple contexts: on the high street, on the gallery wall, in collectors’ homes. Dinsdale argues that the “message of love and acceptance” behind these symbols elevates them – wherever they are. “Perhaps as a design on a Uniqlo T-shirt, his work is in danger of becoming more a signifier of the T-shirt wearer’s cultural capital than anything else,” she says. “But I like to think Keith Haring’s visual language of dancing dogs and radiant babies is powerful enough to communicate something of his original intention, wherever you encounter it.”

Even Grogan believes these items have an advantage over most fast fashion. “I hope that these designs are so cool people will wear them longer,” she says, “because the materials they are made from – cotton blends – aren’t going anywhere.”