Kazimir Malevich / Kasimir Severinovich Malevich

Widely regarded as both one of the most innovative and notorious names in art history, Kazimir Malevich was the originator of the artistic and philosophical school of Suprematism, a movement that was pretty much a one-man show and in that sense very similar to the circumstances surroundings the Fauvism. Although Malevich worked in a huge variety of styles, his most significant and influential efforts focused on the investigation of pure geometric forms such as squares, triangles and circles, as well as their relationships to each other within the pictorial frame. These kinds of innovations led Kazimir to an aspect he liked to call the zero point of a painting. The main intention of Malevich's efforts was to prove that an artist mustn't under any circumstances imitate, but only create - a revolutionary idea that went against almost everything both academic and modern art stood for.

Early Life and the Peasant Art

With a full name of Kazimir Severinovich Malevich, this artist was born on the February 23, during the year of 1878. He became a part of a family that lived near Kiev, only back then the area was called The Kiev Governorate and served as a crucial administrative division of the Russian Empire. Kazimir's parents were called Seweryn and Ludwika Malevich, both of them native Poles, which basically meant their son would be baptized in the Roman Catholic Church unlike most of their neighbors and the local populace. Kazimir was actually the first of fourteen children, although only nine of the Malevich kids survived into adulthood - supporting such a large family was a challenge financially, but since Seweryn was the manager of a sugar factory, the Malevich residency did not struggle as much as you may expect. However, due to the dynamics of the father's occupation, Kazimir had to move a lot and was forced to spend most of his youth in the villages of Ukraine amidst sugar plantations.

It is extremely ironic that one of the most influential modern painters grew so far away from any sort of a cultural center and did not even see a classical piece of art until he turned the age of 13 - however, he did witness a lot of primitive peasant art that might have served him even better in the long run. Malevich was delighted by the rustic adornments of the village, by all the decorated walls and stoves that were meant to brighten up the rural vibes gripping the peasant's everyday life. Although no one saw it coming, Kazimir developed an affinity towards art and soon convinced his father to let him go to Kiev, where Malevich studied drawing between the years of 1895 to 1896. After he graduated, Kazimir found himself in the midst of a standard situation for many modern artists - Malevich was unsure if he should be a part of the family sugar empire or if he should pursue his dreams of being a professional painter. The inner dispute was settled when Seweryn suddenly passed away during the year of 1904 and Malevich made a choice to follow his heart. He left the business in the safe hands of his numerous brothers and decided to give himself a shot at achieving the things he desired the most.

Malevich experimented with many styles prior to discovering Cubism that eventually proved to be the key moment that led him down the path of Suprematism

A Move to Moscow and His Influences

Just after his father's passing, Malevich moved to Moscow in order to attend classes at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. Kazimir studied here from 1904 to 1910, spending his free time at the studio of Fedor Rerberg where he was for the first time exposed to the radical contemporary concepts and ideas Russian modern art had to offer. As every aspiring artist before him, Kazimir had to start small and build his reputation with petite steps, especially logical when you consider that the Russian capital did not admire art as much as their western creative rivals did. In 1911, he participated in the second exhibition of the group The Union of Youth in St. Petersburg, alongside Vladimir Tatlin, where Kazimir was far from the focal point but got himself noticed; in 1912, the same group held its third exhibition, which also included works of Aleksandra Ekster, Tatlin and others. As he was working under the wings of the Union, Malevich was highly influenced by the art of Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, Russian avant-garde painters who were particularly interested in Russian folk art called lubok. Kazimir also acknowledged that his fascination with aerial photography and aviation had a strong influence on his early works and that they had a huge part to play in Malevich's sudden turn to abstraction that was about to happen - he was also a fan of Futurism, an Italian movement that will soon be branded as fascistic due to the ideas of their creative leader, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.

During the March of 1913, a historically significant show of Aristarkh Lentulov's paintings opened in Moscow - the effect of this exhibition was akin with that of Paul Cezanne in Paris in 1907, as all the main Russian avant-garde artists of the time (including young Malevich) immediately absorbed the cubist principles and began using them in their works, testing themselves if they would be able to at least be equally successful as the westerners. These influences eventually led Kazimir to a journey to and exploration of Paris, where the young painter exhibited his work at the iconic Salon des Independants. This was a crucial time in art history, as the period before the start of the First World War was one of the rare times that both the east and the west Europe worked together in order to make their art grander.

Suprematist Ideas

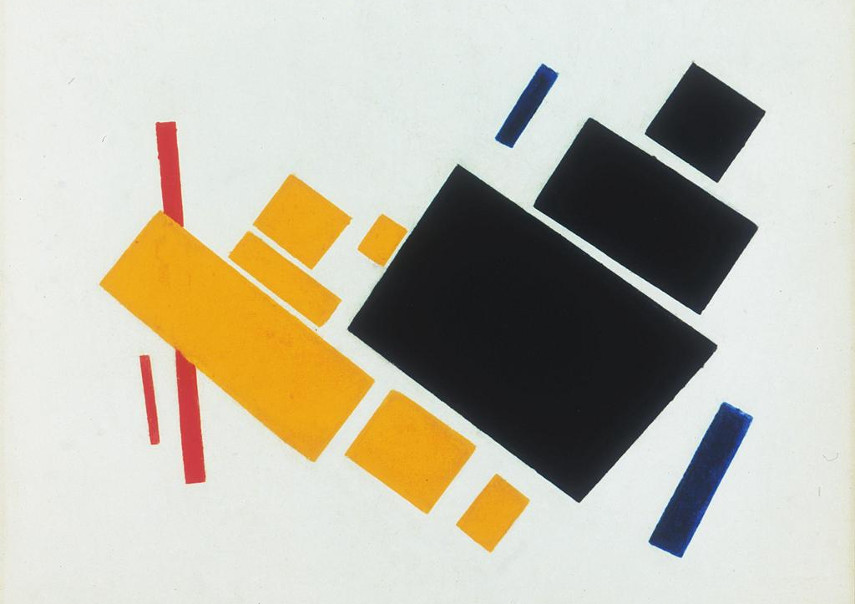

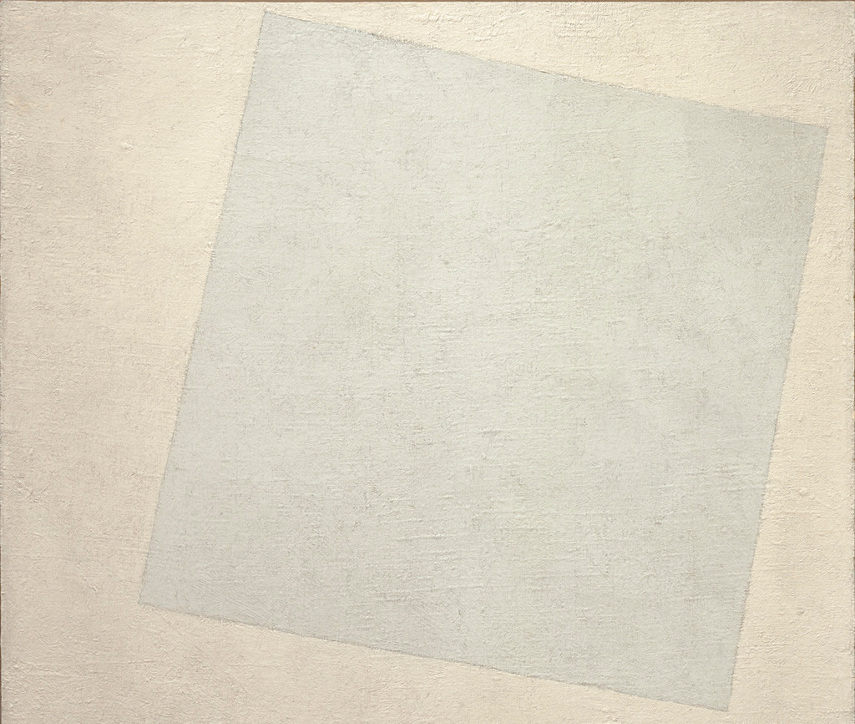

It remains as one of the great mysteries of the 20th-century art, how and why, while leading a comfortable career of simply following all the latest trends in Europe, Malevich suddenly came up with the idea of Suprematism during the summer of 1913. As the war was getting constantly worse and worse, Malevich laid down the foundations of Suprematism when he published his manifesto, titled as From Cubism to Suprematism. Not much is certain about how and why these sudden changes in style came to be, but what is known is that Kazimir worked with other Suprematist artists in a peasant/artisan co-operative in Skoptsi and Verbovka village during the same year manifesto was published. Famous examples of the earliest Suprematist works include the two arguably most renowned paintings Malevich ever created: Black Square (1915) and White on White (1918). On the crossings between the years of 1916 and 1917, Kazimir participated in exhibitions of the Jack of Diamonds group in Moscow together with Nathan Altman, David Burliuk and Ekster, among others.

Many of the critics derived Malevich for approaching art by negating everything good and pure, such as the concepts of nature, life and love. Malevich famously responded that art can advance and develop on its own and for its sake alone, regardless of its pleasure: art does not need us and it never needed us since stars first shone in the sky. He basically meant that we were too full of ourselves and that we truly believed the art was unable to fend for itself. In the year of 1919 came the most important show in the history of Suprematism - an exhibition in Moscow that was literally a one man show and that man was no other than Kazimir Malevich. Through his established works, the artist wanted to reach the zero point of the painting, to somehow release the core of the piece by striving towards simplicity. Although he painted many pieces during the years and many of them had forms as well as realistic subjects, the most influential paintings he authored were the colored surfaces through which Kazimir unleashed two or three colors and effectively reached the aforementioned zero point of the painting. The color was used as a method of communication while the strict geometric forms served as the core of the piece. Malevich liked to call his artworks contra-compositions, disregarding the previous ideas he considered to be gripping the traditional art. An interesting fact is that Kazimir had an opinion that art is utterly useless, so he did not seek any political or social ideas to place them behind his work.

Through painting the modern masterpieces of Suprematism, Kazimir Malevich featured what he liked to call the zero point of painting

Kazimir After the October Revolution and It's Propaganda

Following the ending of the famous October Revolution, Malevich became a member of the Collegium on the Arts of Narkompros, responsible for the protection of public monuments and the collections found in national museums. Besides that important role in the Russian art society, Kazimir also taught at the Vitebsk Practical Art School, the Leningrad Academy of Arts, the Kiev State Art Institute and the House of the Arts in Leningrad. However, soon after that, Malevich's deepest fears became a reality - his assumption that a shifting in the attitudes of the Russian authorities towards the modernist art movement would take place after the death of Lenin were proven correct when the Stalinist regime turned against all forms of abstraction, recognizing them as the worst type of bourgeois art and not capable of expressing any social realities. The art in Russia from that point on was based on Communism and anything that strayed away from its concepts was considered to be dangerous - for those reasons, much of Malevich's work was confiscated and he was banned from creating and exhibiting similar art, which naturally led the enraged artist to a creative stagnation.

Luckily for the art scene, Kazimir wrote the book titled The World as Non-Objectivity, which outlined his Suprematist theories and made sure that his ideas were not in danger of being forgotten. However, the treatment that Kazimir went through during his career remained a stain on the Russian art history, as Kazimir never truly got over the way his countryman behaved towards his works. Nevertheless, he believed in Communism and gave up all the aspects of his work that the regime did not approve off. Despite giving up on all Suprematist ideas, Kazimir was very famous on the national level, but he was waiting for an opportunity to establish his reputation on the international scene - he was presented with a possibility in the year of 1927 when he was expected to travel to Berlin and Munchen for a retrospective which finally brought him global recognition. He was so satisfied with the treatment by the German art scene that Kazimir even arranged for the most of his paintings to stay behind him as he made a trip back to the Soviet Union. Malevich died of cancer in Leningrad on May 15, 1935. The legend says that he was presented with the legendary black square above his deathbed. Inside Malevich's unpublished manifest, the artist stated the following: No phenomenon is mortal and this means not only the body but the idea as well, a symbol that one is eternally reincarnated in another form which actually exists in the conscious and unconscious person.

After the events of The October Revolution, Malevich canceled every Suprematism tour and arts exhibition he had planned due to the regime's desires that all the artists stop creating any form of abstract work

Malevich and His Squares Have Wrote History

Lyubov Popova once said that an artist must not paint realistically, stating that one must separate that what is necessary inside a painting from what is redundant in order to achieve the maximum level of artistic expression. That theory is a hand in glove fit with the concepts of Kazimir Malevich - this artist strived for a simple and unique language unlike anything before him, through which he literally stripped all the unnecessary elements that were useless to him. He formulated the perfect non-figural art, the ultimate level of creative efforts and goals - he believed in his alternative ideas so much that he even had his coffin covered in Suprematism squares, triangles and circles. Such commitment only serves as the exclamation point that stands at the very end of Kazimir's tale, finishing one of the most interesting and crucial stories art history has ever seen.

Featured Image: Kazimir Malevich - Photo of the artist inside his laboratory, 1932 - Image via thecharnelhouse.org

All images via kazimir-malevich.org

Can We Help?

Have a question or a technical issue? Want to learn more about our services to art dealers? Let us know and you'll hear from us within the next 24 hours.